One day at the last Schubertíada I was listening to Schubert’s Die abgeblühte Linde and a motif at the beginning of the second stanza (“Ändrung ist das Kind...”) sounded familiar to me. The second stanza's repetition brought to mind Brahms. These few notes reminded me of a phrase found in two Lieder (which we also heard at the Schubertíada): Sommerabend and Mondenschein. The composer could have quoted Schubert voluntarily or involuntarily because he knew his music very well.

And that's where I wanted to go today, to Brahms' love of Schubert's music. A love that was not at first sight, but came with time. So he told his friend Adolf Schubring in a letter from June 1863:

“My love for Schubert is a very serious one, probably because it is no fleeting fancy.”

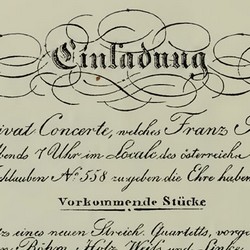

It seems that his first contact with the music of the apple of my eye was through his teacher Eduard Marxen, who had been a student of Karl Maria Bocklet, who had a good relationship with Schubert. We know that in 1853 he attended in Leipzig, with Schumann and Joachim, to an interpretation of the Symphony No. 9, “The Great” and was delighted; we also know that in those years he performed Schubert's chamber works in his concerts.

In April 1861, Brahms accompanied Stockhausen in several performances of Die schöne Müllerin, and in July the baritone gave him the complete edition of Schubert's Lieder, in six volumes. A few months later, the composer arranged for baritone and orchestra a few songs, as requested by his fried to perform them on a concert tour: Memnon, An Schwager Kronos, Geheimes, Gruppe aus dem Tartarus, Ellens Gesang II and Greisengesang. If I am not mistaken, this unusual commission was the first arrangement Brahms made of Schubert's works.

Then came the first visit to Vienna, from September 1862 to May 1863. The letter I mentioned a little above to Schubring continued like this:

“Where is genius like his, which soars heavenwards so boldly and surely, where we see the few supreme ones enthroned. He is to me like a son of the gods, playing with Jupiter’s thunder, and also occasionally handling it oddly. But he plays in such a region, at such a height, to which the others are far short of raising themselves. […] I hope now we shall presently be able to chat about this loved one of the gods.”

In his first stay in Vienna, Brahms had the chance to have some Schubert's original scores in his hands, something that moved him as much as it worried him. How was it possible that those manuscripts were carelessly kept and collected dust?

Ferdinand Schubert had put Diabelli in charge of a part of his brother's work, the one that could be best sold (works for piano, chamber music, Lieder...), which had been edited and published over the years. However, more than thirty years after his death, there were still works that were awaiting publication, both in the hands of various publishers and in the hands of the family. Publishing these scores required time for study, searching for possible copies and corrections, making difficult decisions, and a well-edited version that could be brought to the printing press.

Brahms was one of those who contributed to it. The first publication appeared in 1864, 12 Ländler, Op. 171, which Otto Deutsch later catalogued as D 790. Then, that same decade came the Drei Klavierstücke, D 946 and Der Strom, D. 565 (1868); the 20 Ländler (1869, corresponding to D 366 and D 814) and the Quartettsatz (1870, the first movement of the String Quartet in C, D 703, of which parts of the second are preserved). Finally, Brahms became deeply involved in what would be the first complete edition of Schubert's works, thirty-nine volumes published between 1884 and 1897, and took over the edition of the symphonies.

In addition to the Lieder he orchestrated for Stockhausen, Brahms made arrangements for Schubert's other works; this was one more way to spread the music. Ellens Gesang II, our song this week, is one of them. This song had already been adapted for the baritone, but about ten years later, he adapted it again for a soprano, women's choir, four horns, and two clarinets. The reason for this unusual instrumental accompaniment is found in the text, addressed to a hunter. In Walter Scott's work The Lady of the Lake, Ellen sings this song to entertain her guest, a gentleman who has introduced himself as James Fitz-James, but is actually King James V, a foe to his family (I will tell you the whole story of this work someday). Ellen's Gesang II will be performed by Veronique Gens and the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir conducted by Michel Plasson.

Naturally, Brahms' love for whom he described as "loved one of the gods" is shared here on Liederabend. This week, 196 years after Franz Schubert's death, is a good time to thank him for his music once again.

Jäger, ruhe von der Jagd!

Weicher Schlummer soll dich decken,

Träume nicht, wenn Sonn' erwacht,

Daß Jagdhörner dich aufwecken.

Schlaf! der Hirsch ruht in der Höhle,

Bei dir sind die Hunde wach,

Schlaf, nicht quäl' es deine Seele,

Daß dein edles Roß erlag.

Jäger ruhe von der Jagd!

Weicher Schlummer soll dich decken;

Wenn der junge Tag erwacht,

Wird kein Jägerhorn dich wecken.