On 26 March 1828, Franz Schubert gave his only public concert. That's to say, public because the only requirement to attend it was to buy a ticket, as opposed to the private concerts in somebody's house, limited to those people invited by the host (and invitations were much requested if Schubert was expected to play).

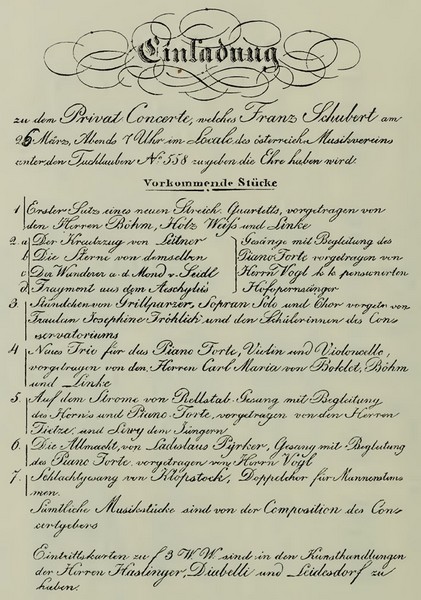

At the top of the article, there is the programme leaflet for that concert (click on the image to enlarge), a reproduction of the only surviving sample. It belonged to pianist Rudolf Serkin, and Sotheby's sold it a few years after his death for 25,000 GBP to an unidentified person. As you can see, it reads about a "Privat Concerte", which took place in the "locale des österreichen Musikvereins". In this context, private means that the concert wasn't organised by the Musikverein, but by one of its members.

The Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, also known as the Musikverein, was founded it in 1812 by Joseph Sonnleithner; the name may be familiar to you, because he, his brother Ignaz and nephew Leopold became eventually friends with Schubert. Our composer requested admission in 1818 as a piano accompanist, and he was turned down because he was not an amateur musician but a professional performer and composer. That's odd, because other professional musicians were members, so there were, possibly, other reasons for not accepting him. Four years later, in 1822, Schubert tried again, this time as a violist and pianist, and he was admitted; finally, in 1827 he was promoted and became a member of a commission that, among other things, had decision-making power regarding the programmes of the concerts. At the time, the Society used to programme four symphonic concerts per year and a series of chamber music called Musikalische Abendunterhaltungen (Musical Evening Entertainment). Symphonic concert were the really important, and were within reach of very few composers; the young Schubert (as many composers or performers) hoped to have his works performed at the Abendunterhaltungen and become his fees. Because the other concerts, the private at the salons, didn't bring him not even a florin, no matter how many people gathered. You see, work in exchange for visibility wasn't created in the 21st century.

I assume that the members of the Musikverein had the right to rent the concert halls, at least a member with influential friends such as Schubert, and in 1828 a project that he and his friends had in mind for years took finally shape: a concert fully devoted to his music. It was initially scheduled for 21 March, but it was postponed because one of the musicians had an indisposition; the date printed on the leaflet is the 29 March, but there's a pencil correction, because the concert was finally on 26 March, the day of the first anniversary of Beethoven's death (we don't know if it was by chance or an hommage)

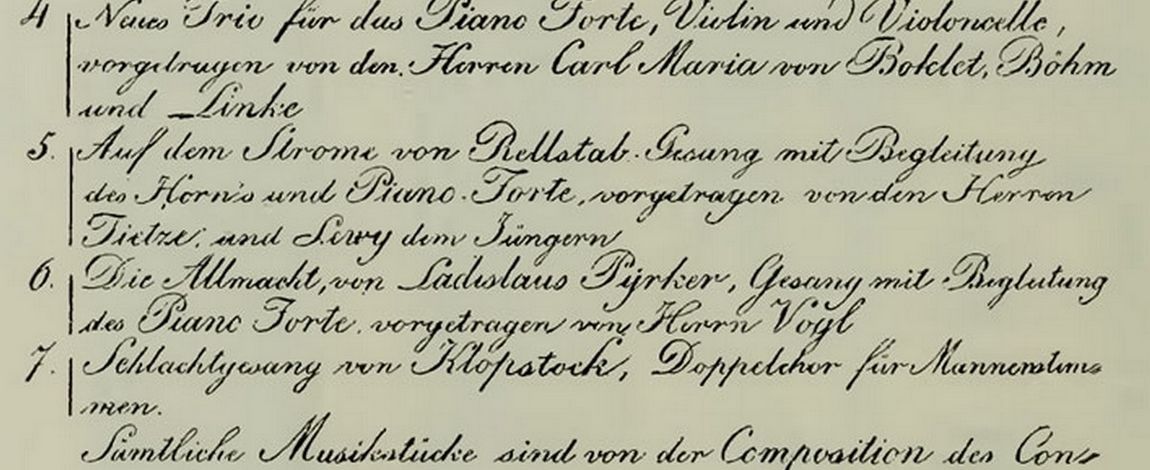

Schubert joined some renowned musicians, kept for himself the piano, and drew up a programme with chamber music and Lieder, that included works already premiered, pieces composed some time ago that were premiered on that day and works that he wrote on the occasion of that concert. You can read the works and the performers on the image, and I list them with the names and catalogue numbers we know today:

String quartet, D. 887 (or maybe String quartet, D. 810), first moviment

Der Kreuzzug, D. 932

Die Sterne, D 939

Fischwerweise, D. 881b (instead of Der Wanterer an den Mond, D. 870; last time changes aren't things of our days, either!)

Aeschylus, D. 450 (fragment)

Ständchen, D. 920

Piano trio, D. 929

Auf dem Strome, D. 943

Die Allmacht, D. 852

Schlachtlied, D. 443

The concert was promoted on the newspapers, all the tickets were sold, it was successful and Schubert got a considerable amount of money (at least, given his usual incomes). And what did the Viennese press say? Nothing at all, because any critic attended the concert. Or, if someone did it, his review had no room in the newspapers because there was a name that drew all the media attention: Paganini. It turns out that the great and celebrated violinist had arrived in Vienna on 16 March to make a series of concerts, the first of which was on 29, and the press only had eyes for him (this is also familiar to us, isn't it?) The only review that Schubert's concert had was published at the Allgemeine musikalischen Zeitung in Berlin; the critic said, with disdainful tone, that the concert had been succesful because the claque of the composer was there.

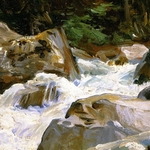

One of the works composed for the concert was the Lied Auf dem Strom (On the River). The poem, which tells of the sadness of a farewell, is by Ludwig Rellstab, the first in a not very long but well-known series (including the first part of the Schwanengesang). The particularity of this Lied is that it wasn't conceived as hausmusik but as a concert piece, because of its length, difficulty and accompaniment, with obbligato horn. It was performed by tenor Ludwig Tietze (yes, THAT Tietze), horn player Josef Rudolf Lewy and, as I said, Schubert at the piano, and was repeated a few weeks later in a concert organized by the horn player.

Given that Schubert wrote in October one more Lied of similar structure, the much better-known Der Hirt auf dem Felsen, with obbligato clarinet, we could think that he might have wanted to explore this new path, but, as you know, there was no time for more, as there was no time for a new public concert: Schubert died on 19 November. The week this article marks 193 years of his death, let's remember him and be greatful for his music!

A few weeks after his death, on 31 January, the day he would have turned thirty-two, his friends organized a concert to pay tribute to him. Among the plays performed there was Auf dem Strom, but this time with cello obbligato; shortly afterwards the score was published, with both versions, cello and horn. And a couple of years later, Diabelli published a new version, only for voice and piano.

Auf dem Strom is an unusually long Lied; I prefer not share such long pieces (about ten minutes), but this time I thing it's worth it, so we're listening to the original version, performed by baritone Nikolay Borchev, horn player Kevin Rivard and pianist Wu Han.

I leave you with the music of the apple of my eye, and I'll try to prepare something shorter for next week.

Nimm die letzten Abschiedsküsse,

Und die wehenden, die Grüsse,

Die ich noch ans Ufer sende,

Eh’ Dein Fuss sich scheidend wende!

Schon wird von des Stromes Wogen

Rasch der Nachen fortgezogen,

Doch den tränendunklen Blick

Zieht die Sehnsucht stets zurück!

Und so trägt mich denn die Welle

Fort mit unerflehter Schnelle.

Ach, schon ist die Flur verschwunden,

Wo ich selig Sie gefunden!

Ewig hin, ihr Wonnetage!

Hoffnungsleer verhallt die Klage

Um das schöne Heimatland,

Wo ich ihre Liebe fand.

Sieh, wie flieht der Strand vorüber,

Und wie drängt es mich hinüber,

Zieht mit unnennbaren Banden,

An der Hütte dort zu landen,

In der Laube dort zu weilen;

Doch des Stromes Wellen eilen

Weiter ohne Rast und Ruh,

Führen mich dem Weltmeer zu!

Ach, vor jener dunklen Wüste,

Fern von jeder heitern Küste,

Wo kein Eiland zu erschauen,

O, wie fasst mich zitternd Grauen!

Wehmutstränen sanft zu bringen,

Kann kein Lied vom Ufer dringen;

Nur der Sturm weht kalt daher

Durch das grau gehobne Meer!

Kann des Auges sehnend Schweifen

Keine Ufer mehr ergreifen,

Nun so schau’ ich zu den Sternen

Auf in jenen heil’gen Fernen!

Ach, bei ihrem milden Scheine

Nannt’ ich sie zuerst die Meine;

Dort vielleicht, o tröstend Glück!

Dort begegn’ ich ihrem Blick.

Take the last parting kiss,

and the wavy greeting

that I'm still sending ashore

before you turn your feet and leave!

Already the waves of the stream

are pulling briskly at my boat,

yet my tear-dimmed gaze

keeps being tugged back by longing!

And so the waves bear me forward

with unsympathetic speed.

Ah, the fields have already disappeared

where I once discovered her!

Blissful days, you are eternally past!

Hopelessly my lament echoes

around my fair homeland,

where I found her love.

See how the shore dashes past;

yet how drawn I am to cross:

I'm pulled by unnameable bonds

to land there by that little hut

and to linger there beneath the foliage;

but the waves of the river

hurry me onward without rest,

leading me out to the sea!

Ah, before that dark wasteland

far from every smiling coast,

where no island can be seen -

oh how I'm gripped with trembling horror!

Gently bringing tears of grief,

songs from the shore can no longer reach me;

only a storm, blowing coldly from there,

can cross the grey, heaving sea!

If my longing eyes, surveying the shore,

can no longer glimpse it,

then I will gaze upward to the stars

into that sacred distance!

Ah, beneath their placid light

I once called her mine;

there perhaps, o comforting future!

there perhaps I shall meet her gaze.

Comments powered by CComment