Heinrich Panofka was best known as a voice teacher. In 1842, he founded an academy with tenor Marco Bordogni in Paris, and in 1855, he published his method, L'art de chanter. He was also renowned as a music critic; for example, he wrote in Schumann's "Neue Zeitschrift für Musik" or "Revue et gazette musicale" (where an article on Schubert in 1838, contributed to the dissemination of his music in France, complementing the work of Franz Liszt, Adolphe Nourrit, or Chrétien Urhau).

Although Panofka specialized in singing over the years, his career had begun as a violinist. Born in 1807 in Breslau, he excelled at the violin as a child, to the point where he debuted in a concert at the age of ten. In 1824 he began studying law at his city's university, as his father wished, but as soon as he had finished he packed his bags and made his way to Vienna, to study with violinist and composer Joseph Mayseder, to whom even Paganini praised.

Heinrich arrived in Vienna in 1827. Like many students of the time, he had an autograph album where friends, colleagues, and personalities wrote some lines, some music notes or a small drawing with a dedication. At a time when it was hard to keep in touch with acquaintances, those albums were a memory, and they were also a kind of letter of introduction. The pages of the album of Panofka should be filled with ease in Vienna, because he achieved great success as a concert performer; enough to get him hired to tour Germany. However, he found that his life was not satisfying, and in 1834 he left for Paris. Of course, he had the autograph album in his suitcase. Its pages included, for example, a carefully pasted fragment of Beethoven's String Quartet No. 14 from the composer's hand; which was probably a gift from Anton Schlindler, his secretary. And there was also a little Schubertian treasure.

Schubert and Panofka's relationship is unknown, whether they deal with each other often or not. The point is that Schubert filled three pages of the autograph album with the score of a lied, Herbst [Autumn], and added the dedication “Zur freundlichen Erinnerung” [As a friendly memory] and the date, April 1828. Later, Panofka added the composer's dates of birth and death, included a small portrait of him and also an envelope where he had written: "Fleurs de la tombe de F. Schubert" [Flowers from the grave of F. Schubert].

Panofka lived in Paris and London, and continued to collect autographs from composers: Hummel, Liszt, Paganini, Brahms. In 1866, he retired and moved to Florence, where he died in 1887. It appears that before leaving Paris, he gave away his album and someone else continued to collect autographs. It seems strange to me, but I would say he didn't have any children who could keep it, and maybe he gave it to someone very dear to him. Maybe he no longer found pleasure in browsing through its pages. After his death, the book reappeared, and that little Schubertian treasure became a great treasure. Nobody was aware of the existence of that song, Herbst. The copy that Panofka had was the sole one. Can you imagine how excited the musicologists were when they found it? The song was published at the last minute in the Gesamtausgabe, the first complete edition of Schubert's works, in 1895.

Herbst's poem is by Ludwig Rellstab, one of those that the poet sent to Beethoven after visiting him in Vienna, which eventually went to Schubert. From those sheets came the composer's ten lieder with Rellstab's poem: the seven from Schwanengesang; Herbst; Auf dem Strom, with horn obbligato, which we heard some time ago, and Lebensmut (a mental note: to tell about this song one day). During the spring and summer of 1828, all of them.

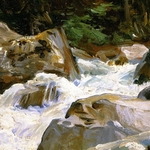

For both the theme and the music, Herbst may have been another song from the Schwanengesang. The poem draws a parallel between the arrival of autumn, which takes away all the good things spring had brought, and the loss of love. Every two stanzas of the poem were grouped together, and Schubert wrote a pure strophic song with the new three stanzas. In the first two, the first part describes a moment in autumn (the fall of the leaves, the clouds) and the second part describes the feelings the poet has at this moment. In the third stanza, both things are mixed at the beginning. At the vocal line, the first part of the stanza is quieter, more “narrative”, while at the second part, the lament, the phrases are wider and the repetitions emphasize the pain. From the beginning to the end of the song, the piano movement reminds us of the wind, the clouds that run through the sky, and the leafs that swirl on the ground. It is a beautiful song that we are listening to from one of our favourite baritones in this place, Florian Boesch, accompanied by Roger Vignoles.

It appears that, after the false start in early September, autumn has arrived this time. Or an approach in the autumn, which is usually what we have in Barcelona. Well, we'll see...

Es rauschen die Winde

So herbstlich und kalt;

Verödet die Fluren,

Entblättert der Wald.

Ihr blumigen Auen!

Du sonniges Grün!

So welken die Blüten

Des Lebens dahin.

Es ziehen die Wolken

So finster und grau;

Verschwunden die Sterne

Am himmlischen Blau!

Ach, wie die Gestirne

Am Himmel entflieh’n,

So sinket die Hoffnung

Des Lebens dahin!

Ihr Tage des Lenzes

Mit Rosen geschmückt,

Wo ich die Geliebte

An’s Herze gedrückt!

Kalt über den Hügel

Rauscht, Winde, dahin!

So sterben die Rosen

Der Liebe dahin!

The winds are sweeping,

so autumnal and cold;

empty are the fields,

leafless the woodland.

You flowery meadows!

You sunny green space!

So do the blossoms

of life fade away.

The clouds are drifting,

So gloomy and grey;

Vanished are the stars

From the ethereal blue!

Ah, as the stars

Escape from the sky,

So does the hope

of life recede away.

You days of springtime,

decked with roses,

during which I pressed my beloved

to my heart!

Coldly over the hill,

oh winds, rush in!

So do the roses

of love die away.

(translation by Emily Ezust)