For his part, Wagner highly admired Schubert. Those weird harmonies that appeared here and there in his first (six hundred) Lieder weren't just experiments, and over the years his evolution came dangerously close to what Brahms called the "New German School." So dangerously that it was difficult for him to justify the premiere of some of Schubert's works in the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, where he was supposed to programme only the most orthodox composers. But the most serious danger was to make Clara Schumann angry as she hated anything which could be somehow related to Wagner! She, who premiered Schubert's first piano concert (Robert as the conductor) and so many sonatas, refused to play his last three (his very last three sonatas, not the three last from his first period).

I haven’t spoken about Lied yet. For your peace of mind, let me tell you that he never stopped writing songs. They were part of his own nature. For him, songs, just as pieces for piano four hands or quartets, were music to be shared. To be edited and sold, too, of course, but making music with the people he loved always made him happy. The family quartet lasted until their father's death, in 1830, but those evenings with his brothers Ferdinand and Ignaz continued, and many friends, among them the most brilliant musicians, such as Joseph Joachim, loved to play the new pieces. Joachim also got something really great from those meetings (and we'll always be grateful to him for that): he insisted until Franz wrote two new concerti: a violin concerto and a viola concerto. Have you ever thought how much a viola suits Schubert? Willing to express his gratitude, the violist gave him something that really surprised him: the orchestration of his Sonata for piano four hands. Joachim and Schumann always thought that its score concealed a symphony.

Schubert was not surprised but astonished when Brahms, the day they first met, asked him with bright eyes to accept a little gift. He looked at Geheimes score... orchestrated! Then, back at the young man, then again at the score and he couldn't utter a single word. Finally, with great care, he gratefully acknowledged his gift. Sometime later, when they were close friends, he could express himself freely: Johannes, for God's sake, an orchestral Lieder!? But... why!? What's the point!? Schubert didn't understand it at all, as he didn't understand those massively attended song recitals either that, gradually, became fashionable. Everything had begun on 4 May 1856, when baritone Julius Stockhausen gave his first complete performance of Die schöne Müllerin, for more than two thousand people. Needless to say, the composer was invited, but at the last moment his aches and pains of old age stop him from attending (those convenient aches and pains of old age were some of the few privileges he allowed himself; everybody knew that he was horrified by public recognition!) Next day, the concert was repeated, and again, sold out. That time, Schubert was there, incognito, with the caretaker’s complicity, and he was moved to tears by the audience’s response. He couldn't stand being in the limelight, but these people fondness, his neighbours, was a completely different thing.

Stockhausen and Brahms... Franz soon realized that little could be done except from letting thing be. He wrote Lieder, he shared those Lieder with his friends as he had always done, he published them, and if those two wanted to perform them in extravagant places of ways, well, that was their business. He always paid attention to the latest publications, and when he heard the music of a new volume of poetry, he was intensely devoted to it. For example, after writing dozens of Lieder from Heine's Buch der Lieder (Schumann and him used to tell each other, in their letters, which poems have they musicalized), he didn't miss the publication of Neue Gedichte in 1844 and Romanzero six years later. He was especially interested in new authors, he carefully read Eichendorff's poems in 1837 and Mörike's some months later. He wrote very fine Eichendorff's Lieder, but Mörike words stimulated his boundless imagination and reached his deepest tenderness and most contemplative moments.

And so, years went by, from poet to poet. Schubert returned only twice to his youth poets. The first time, it was due to a tragic circumstance, the death of Johann Mayrhofer. Although he knew well his friend, his depressions and his frustrated suicide in 1830, it was a terrible blow when he finally took his life in 1836. He didn't write a single note for months. One day, somebody left Mayrhofer's poems on the piano, that verses that almost belonged to both, so close was their relationship when Johann wrote them. One after the other, he wrote twenty-two Lieder, the song cycle Der Fernen, entitled according to one of the poems he had chosen.

The second return to his old literary references was in 1849, when the German culture celebrated the centenary of Goethe's birth. Liszt, responsible for the homage in Weimar, and Schumann, who contributed with his Scenes from Goethe's Faust in Dresden, wrote him to ask for his contribution. Schubert did not feel like going back more than twenty years, but one night he got up and thumb through the two manuscript collections he had sent to the great poet and had been returned without a comment, not even an impersonal note from his secretary. One was dated in 1815 when nobody except for his enthusiastic friends knew him; the other one in 1825, when he began to be known in musical circles in Germany. he sighed, rose up and went to fetch Goethe's poems in his library...

The only constant poet throughout his long life was Friedrich Rückert. He anxiously awaited every new poetry volume and read it from cover to cover, and his Rückert's lieder were always as splendid as those he had composed in his twenties. He wrote a long collection in 1834, when Liebesfrühling was published, in 1843, with Haus und Jahr, and in 1872, when the poet's widow published the Kindertodtenlieder (or maybe you thought that his Todessehnsucht was a fleeting feeling?) Until the very last day, until that last Lied ended a few hours before dying, Rückert.

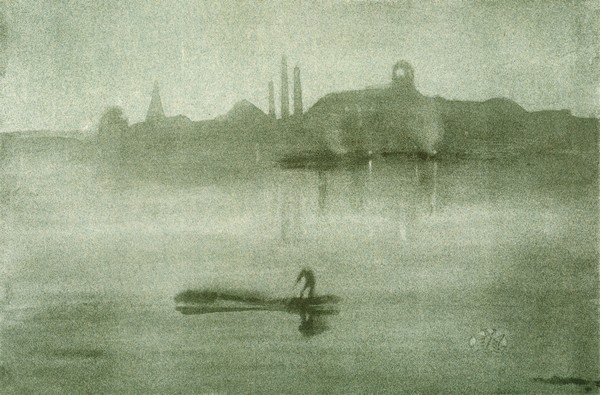

Which music did we miss? Which fairer hopes? Again and again, the same question. Perhaps the strange and fascinating Die Stadt could give us a clue?

Am fernen Horizonte

Erscheint, wie ein Nebelbild,

Die Stadt mit ihren Thürmen,

In Abenddämmrung gehüllt.

Ein feuchter Windzug kräuselt

Die graue Wasserbahn;

Mit traurigem Tacte rudert

Der Schiffer in meinem Kahn.

Die Sonne hebt sich noch einmal

Leuchtend vom Boden empor,

Und zeigt mir jene Stelle,

Wo ich das Liebste verlor.

Upon the far Horizon

Like a picture of the mist,

Appears the towered city

By the twilight shadows kissed.

The moist soft breezes ripple

Our boat's wake grey and dark,

With mournful measured cadence

The boatman rows my bark.

The sun from clouds outshining,

Lights up once more the coast;

The very spot it shows me

Where she I loved was lost.

(translation by Emma Lazarus)

Comments powered by CComment