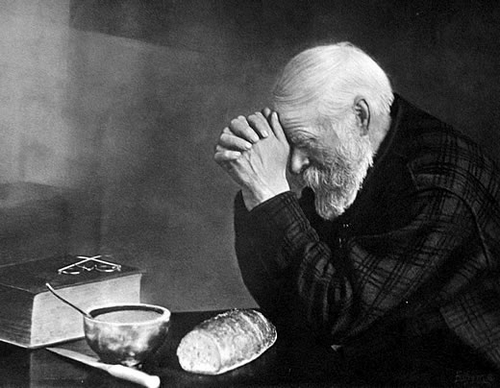

Grace. E. Enstrom

Antonín Dvořák lived in New York from September 1892 to April 1895; he was invited as director of the National Conservatory of Music, with the aim of promoting an American music that looked into its own roots instead of (or in addition to) the European tradition. During this stay he composed his most famous work, the Symphony from the New World, premiered on 16 December 1893. A few weeks after, in March 1894, Dvořák composed the Biblické Písně ( Biblical songs), a cycle of ten songs with texts from the Bible, from the Book of Psalms.

Religious songs are not very usual; religious cycles, even less. We listened to some examples in the last years, at Christmas or Easter. We spoke about just one cycle, the Five Mystical Songs by Ralph Vaughan-Williams, and some day I'll talk about the Gellert-Lieder by Beethoven, the Geistliche Lieder by Wolf (included in the Spanisches Liederbuch) or the Vier ernste Lieder by Brahms, that share with Dvořák's cycle the biblical origin of its texts. According to the named composers, it's not essential to be a religious person to write religious songs (at least Beethoven and Brahms declared not to be believers), but Dvořák was. He also read often the Bible and knew it very well.

However, we don't know for certain why he wrote those songs. Maybe you wonder why there should be a particular reason. That's a good question. In the late 19th century, songs were mostly composed to be performed in a concert hall rather than at home, as usual fifty years ago; On the other hand, Art Song was still a shelter for the composer, where the most intimate feelings were expressed. Since religious songs were not the most suitable for a concert hall, that suggests that Dvořák wrote his Biblical songs for some reason.

Scholars speak of two possible reasons. The first one, the bad news that came from Bohemia: the death of his friend Hans von Bulow on February 12th and the serious illness of his father, who died on March 28th, two days after he ended the songs. Another possible cause is Dvorak's homesickness. From a professional point of view, his life in New York was going well, but he needed to return home. In fact, when his contract expired the following year, he chose not to renew it. By March 1894, he should feel deeply sad, far from home and after receiving such bad news from there; The song I chose to share with you, Popatřiž na mne a smiluj se nade mnou, makes us think of that sadness. It's a part of Psalm 25, verses 16-18 and 20, where the one who prays asks God to console his grief; the verse 19, omitted by the composer, refers to his enemies.

Dvořák orchestrated the first five songs of the cycle in 1895; they were premiered but then the scores were lost (yes, I also wonder how it's possible) and not published until 1914, ten years after the composer's death; that edition included the orchestration of the five remaining songs by Vilem Zemanek. We're listening to the song no. 8, so we're listening to the original version for voice and piano, performed by Bernarda Fink and Christoph Berner.

Dvořák took the texts from the Kralice Bible, a Czech translation from the late sixteenth century; you will see that the original text has a line more than the English text, that I took from the King James Version Bible (published just some years after the Kracile Bible); that's because the composer, after the verse 17, added the words Smiluj se nade mnou of the first verse (Have mercy upon me), the only addition he made in the entire cycle. Was he insisting on his pain? Or was it just for musical reasons?

I hope you enjoy this song and your Easter week!

Religious songs are not very usual; religious cycles, even less. We listened to some examples in the last years, at Christmas or Easter. We spoke about just one cycle, the Five Mystical Songs by Ralph Vaughan-Williams, and some day I'll talk about the Gellert-Lieder by Beethoven, the Geistliche Lieder by Wolf (included in the Spanisches Liederbuch) or the Vier ernste Lieder by Brahms, that share with Dvořák's cycle the biblical origin of its texts. According to the named composers, it's not essential to be a religious person to write religious songs (at least Beethoven and Brahms declared not to be believers), but Dvořák was. He also read often the Bible and knew it very well.

However, we don't know for certain why he wrote those songs. Maybe you wonder why there should be a particular reason. That's a good question. In the late 19th century, songs were mostly composed to be performed in a concert hall rather than at home, as usual fifty years ago; On the other hand, Art Song was still a shelter for the composer, where the most intimate feelings were expressed. Since religious songs were not the most suitable for a concert hall, that suggests that Dvořák wrote his Biblical songs for some reason.

Scholars speak of two possible reasons. The first one, the bad news that came from Bohemia: the death of his friend Hans von Bulow on February 12th and the serious illness of his father, who died on March 28th, two days after he ended the songs. Another possible cause is Dvorak's homesickness. From a professional point of view, his life in New York was going well, but he needed to return home. In fact, when his contract expired the following year, he chose not to renew it. By March 1894, he should feel deeply sad, far from home and after receiving such bad news from there; The song I chose to share with you, Popatřiž na mne a smiluj se nade mnou, makes us think of that sadness. It's a part of Psalm 25, verses 16-18 and 20, where the one who prays asks God to console his grief; the verse 19, omitted by the composer, refers to his enemies.

Dvořák orchestrated the first five songs of the cycle in 1895; they were premiered but then the scores were lost (yes, I also wonder how it's possible) and not published until 1914, ten years after the composer's death; that edition included the orchestration of the five remaining songs by Vilem Zemanek. We're listening to the song no. 8, so we're listening to the original version for voice and piano, performed by Bernarda Fink and Christoph Berner.

Dvořák took the texts from the Kralice Bible, a Czech translation from the late sixteenth century; you will see that the original text has a line more than the English text, that I took from the King James Version Bible (published just some years after the Kracile Bible); that's because the composer, after the verse 17, added the words Smiluj se nade mnou of the first verse (Have mercy upon me), the only addition he made in the entire cycle. Was he insisting on his pain? Or was it just for musical reasons?

I hope you enjoy this song and your Easter week!

Popatřiž na mne a smiluj se nade mnou

Popatřiž na mne a smiluj se nade mnou;

Nebot' jsem opuštěný a ztrápený.

Soužení srdce mého rozmnožují se,

Z úzkostí mých vyved' mne.

Smiluj se nade mnou!

Viz trápení mé a bídu mou

A odpust' všecky hřichy mé.

Ostříhej duše mé a vytrhni mne

At' nejsem zahanben,

Nebot' v Tebe doufám.

Nebot' jsem opuštěný a ztrápený.

Soužení srdce mého rozmnožují se,

Z úzkostí mých vyved' mne.

Smiluj se nade mnou!

Viz trápení mé a bídu mou

A odpust' všecky hřichy mé.

Ostříhej duše mé a vytrhni mne

At' nejsem zahanben,

Nebot' v Tebe doufám.

Turn thee unto me, and have mercy upon me;

for I am desolate and afflicted.

The troubles of my heart are enlarged:

O bring thou me out of my distresses.

Look upon mine affliction and my pain;

and forgive all my sins.

O keep my soul, and deliver me:

let me not be ashamed;

for I put my trust in thee.

for I am desolate and afflicted.

The troubles of my heart are enlarged:

O bring thou me out of my distresses.

Look upon mine affliction and my pain;

and forgive all my sins.

O keep my soul, and deliver me:

let me not be ashamed;

for I put my trust in thee.

Comments powered by CComment