Which thirty-seven-old composer would be invited nowadays by the Berlin Philharmonic to conduct a programme with his own works? After the success achieved in Germany a couple of years earlier with his Third Symphony, Charles Villiers Stanford offered on 14 January 1889 a concert in Berlin where his Fourth Symphony and his Suite for violin and orchestra were premiered; the violinist was no more, no less, than the great Joseph Joachim.

Born in Dublin in 1852, Stanford is one of the composers who mostly contributed to revitalize British music in the late 19th century. Not only with his musical works, but also with his pedagogical work; among his students were Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst, or Frank Bridge, to mention only three that we heard here. His wide work (although only his church pieces are regularly performed) also includes numerous songs, and we listen to two during 2021: Tears and The Monkey's Carol; however, since both coincided with holiday periods, that is, with shorter articles, I didn't introduce the composer. This week we're listening to a third song by Stanford, and I hope the brief introduction about his career will help to put them into context.

The composer devoted himself intensely to Art Song, in a time, the Victorian era, where parlour songs were in great demand. Stanford, however, didn't consider the song a minor genre; in his Musical Composition, published in 1911, he referred to the writing of a good song as “one of the most difficult tasks which a composer can undertake”. The Stanford Society mentions on its website a corpus of three hundred songs, of which, if I'm not wrong, a part isn't recorded yet; recently new CDs appeared and, since 2024 marks 100 years since the composer's death, I expect this anniversary will promote both recordings and concert performances.

That important concert in Berlin in 1889 included three songs, the orchestrated versions of pieces originally written for voice and piano (sadly, the scores are missing); among them, his best-known song, a piece that remained in the repertoire: La belle dame sans merci.

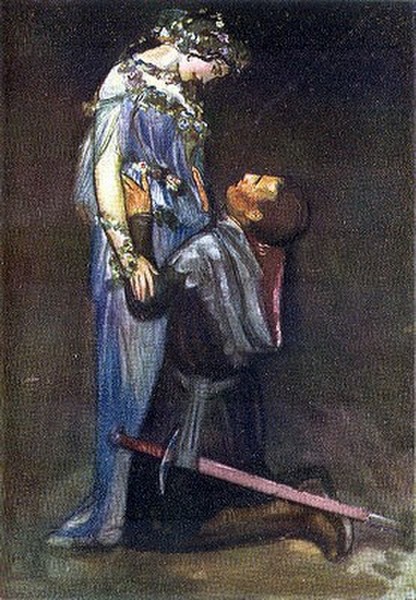

The composer set into music a famous poem written in 1819 by John Keats, the Romantic poet contemporary of Schubert, although he died even younger than him; he died at twenty-six, two years after writing La belle dame sans merci. In the first three stanzas, we hear someone addressing a knight who looks distressed; in the remaining nine stanzas, the knight himself explains how he fell in love with a lady who turned to be a fairy and left him in a miserable situation. In the final part of the poem, the knight tells how other victims of the cruel creature appeared in his dreams, and refer to her as la belle dame sans merci. Keats quotes a well-known French poem, written in 1424 by Allan Chartier (and translated into English in 1460 by Richard Ros); in this work, a young man dies of a broken heart after being repeatedly refused by a beautiful lady without mercy.

Keats's poem is inspired by a medieval ballad, and Stanford, who in 1877 had just returned from his years in Germany and knew well the genre, also gave his song this form. He appears to have written it in a single sitting, and it wasn't until many years after that he realized this hadn't been his first attempt to compose after this poem. In 1892, he found some sketches from 1866, when he was only fourteen, and abandoned the task because it was too difficult for him. However, the remarkable thing wasn't to find those sketches, but to realize that the first three verses of both versions were virtually the same.

I suggest that we listen to an interpretation of La belle dame sans merci I like very much, that of Ian Bostridge and Julius Drake. I hope you enjoy it.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

So lone and palely loitering?

The sedge hath wither’d from the lake,

And no birds sing.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

So haggard and so woebegone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

I see a lily on thy brow

With anguish moist and fever dew,

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child;

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She look’d at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan.

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

‘I love thee true.’

She took me to her elfin grot,

And there she wept, and sigh’d full sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

And there she lulled me asleep,

And there I dream’d—Ah! woe betide!

The latest dream I ever dream’d

On the cold hill’s side.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried—‘La belle dame sans merci

Hath thee in thrall!’

I saw their starved lips in the gloom,

With horrid warning gaping wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is wither’d from the lake,

And no birds sing.

Comments powered by CComment