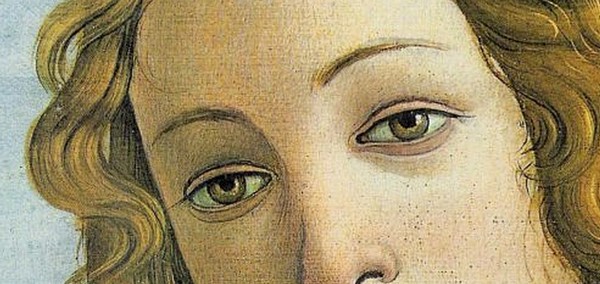

Maria Meyer arrived at Ludwigsburg when a brewer found her senseless on the road and took her home to take care of her; once she recovered she remained as a barmaid. She was a beautiful young woman, everyone talked about her eyes; she was also a good conversationalist and unexpectedly cultured. The young men began to go to the brewery more often than usual, and Eduard Mörike was no exception; he had just arrived at his hometown to spend the Easter holidays and fell in love with Maria. And Maria with him. They were inseparable during Eduard's time at home, and when the holiday ended, and he returned to Tübingen, they continued the relationship by letter.

Maria Meyer was not the kind of girl a family would want for their son. No one knew where she was coming from, or her family, not to mention her reputation. Any respectable family would regard her as a good catch, even less the family of a future clergyman such as Eduard, who at the time studied theology. The young man, then nineteen, kept the relationship with Maria despite everything, but one day, at the end of that year 1823, Maria disappeared. After much searching for her, they knew she had been found in a faint on her way near Heidelberg; either the girl suffered from some illness that caused her frequent fainting fits, or she pretended them to inspire pity. This time, however, she wasn't as lucky as in Ludwigsburg, and she was declared a vagrant and imprisoned for a time. There was more bad news for Eduard: the girl was with another man. As you can imagine, he felt hurt and betrayed; some time later, Maria went back to him, but it was too late.

Maria was not mad, the poet knew it. Her madness was her way of being, so free and indifferent to the rules, so shrouded in mystery. This madness was part of her appeal; as Mörike wrote in one of the poems dedicated to her, Schön war ihr Wahnsinn [His madness was beautiful]. But it also was the reason why he lost his Peregrina, as he used to call her. The series of five poems dedicated to Maria, Peregrina I to V, were published in 1832 as a part of a novel, Maler Nolten [Nolten the painter], similarly to Mignon's or the harpist's poems in Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship.

Hugo Wolf put into music two of the Peregrina poems, the first and the fourth; they are no. 33 and 34 of the Mörike-Lieder, composed both in April 1889, and this week we're listening to the first one. I usually say that Wolf wrote wonderful songs from contemplative poems such as this one: we've listened so far Was für ein Lied soll dir gesungen werden from the Italienisches Liederbuch, or An die Geliebte, the previous song in the Mörike-Lieder, and we confirm that again with Peregrina I. It begins with the indication "sehr getragen (innig)" [very solemn (intimate)] and during the first six verses the music is restrained, sober; the piano plays chords always repeating a pattern, dotted crotchet-quaver, beginning with low notes that rase until they reach the highest ones at "dort mag solch Gold". From there on, low chords again, raising until "tauchen", when they fall suddenly, preparing the ground for the end of the song. Now, for the last two verses, the indication is "leidenschaftlich belebt" [lively with passion], and both voice and piano honour to it.

We're listening to Peregrina I performed by Roman Treckel and Oliver Pohl; I hope you like it as much as I do.

Der Spiegel dieser treuen, braunen Augen

Ist wie von innerm Gold ein Widerschein;

Tief aus dem Busen scheint er's anzusaugen,

Dort mag solch Gold in heil'gem Gram gedeihn.

In diese Nacht des Blickes mich zu tauchen,

Unwissend Kind, du selber lädst mich ein—

Willst, ich soll kecklich mich und dich entzünden,

Reichst lächelnd mir den Tod im Kelch der Sünden!

The mirror of these faithful, brown eyes

is like a reflection of inner gold;

from deep within the bosom it seems to be drawn;

there may such gold thrive in sacred grief.

To plunge myself into the darkness of this gaze,

naive child, you yourself beckon me -

you will me to boldy ignite us both,

with a smile, handing me Death in a goblet of sin!

(translation by Emily Ezust)