Moritz von Schwind arrived at Munich in 1828 to learn under Peter von Cornelius, Professor at the Academy of Fine Arts (two decades later, Schwind also became a Professor at the same art academy). Munich was at that time a much more stimulating place for artists than Vienna, where Schwind was born and had lived until then; King Ludwig I of Bavaria was an art lover (he founded the Glyptothek and the Neue Pinakothek, for example) and there were plenty of opportunities for young painters. After five years of living in Munich, Schwind was commissioned to paint the library frescoes at the king’s new palace and this launched his successful career, which covered from large-scale works to illustrations for almanacs, one of the things that he liked the most. He was passionate about music, poetry and folklore and painted many scenes from works by Goethe, Tieck or Brentano; Cornelius said that Schwind "translated the joy of music into pictorial art."

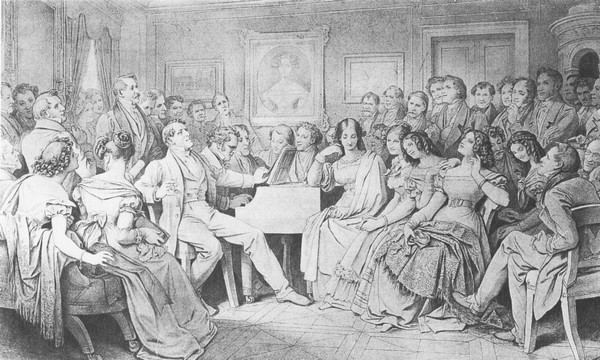

It took our man forty years to return to Vienna, when he painted the frescoes of the foyer and the loggia at the new Opera, opened in 1869; his paintings survived the bombing during the World War II, so don’t’ forget to look up to the ceiling if you ever visit the Staatsoper. During that period he also painted the sepia drawing that heads this article, which I used a few years ago when I talked about schubertiades; this is it’s most popular name, Schubertiade, although the official name is Ein Schubertabend bei Ritter von Spaun [A Schubert-Soirée in the house of Baronet Spaun].

It's believed that the drawing could have been inspired by a soirée that took place at Josef von Spaun’s house on December 15, 1826, attended by Schubert's most intimate circle and many other people, acquaintances of some sort. Spaun had introduced Moritz von Schwind to Schubert in 1821, when the painter was only seventeen and, as he presumed, they became best friends; As a title for this article, I have chosen some words that convey the great admiration that Schwind felt for Schubert's music: "as Schubert composes, so do I want to paint."

Four years ago, also during this week that we commemorate Schubert's death on November 19, 1828, I talked about some of his friends; this year I'm taking up the thread, talking about some of the forty-three people identified in the drawing and, above all, about the way in which Schwind portrays them. As we'll see, he refers to previous episodes and even to other future circumstances; some of the advantages of painting the scene with forty years of perspective.

- The most prominent figure in this scene is not Schubert, but Johann Michael Vogl, who sings seated. Some witnesses explained that the baritone sang more than thirty lieder at that meeting in 1826, which could explain the need for a chair. Schubert is in the background, of course at the piano, and we only see his head and hands; His friends often talked about his discrete behaviour even when he was the one bringing all that people together. To his left, always near him, Spaun.

- Schwind also appears in this painting. Look at the standing men on the right of the wall portrait, he's the third one; next to him other two painters and friends stand: August Rieder and Leopold Kupelwieser, both authors of famous portraits of Schubert. The young lady who listens with that look of enchantment on her face, seated in front of Schwind, is Nettel Hönig, an excellent pianist deeply appreciated by Schubert, who had a love story with our painter.

- Poets are on the right of the painters’ group: Grillparzer, Bruchmann, Senn, Mayrhofer and Bauernfeld. Sadly, Senn couldn't attend that meeting; the authorities had imprisoned and banished him due to his political militancy some years before Schwind met Schubert. But not doubt that he knew that Schubert was really fond of that poet and missed him terribly.

- Sitting in front of the poets, a couple is flirting instead of listening to the music. They are Franz Schober, who should have been among the poets, and Justine, Franz von Bruchmann's sister. Schwind refers to an unpleasant situation they lived through in 1824: Schober and Justine got engaged secretly, because Schober wasn't the gentleman that Bruchmann wished for his sister (of course, her opinion was not relevant). When Bruchmann found out about the engagement, he forced them to break it, and the circle lived some strained episodes, as usually happens when loyalties are at stake among friends.

- On the lower left side on the drawing we can see a lady’s profile portrait. This figure is another anachronisms in this composition: she's Eleonore Stohl, an outstanding Schubertian singer who was not born until 1832. She used to sing with pianist Josef Gahy, who was Schubert’s friend; they often play together works for four hands. We can also find him on the drawing: do you see the tall man behind Vogl? He is Baron of Schönstein, an amateur singer very close to Schubert; the second head on his left is that of Gahy.

- To finish off this review, let's talk about the wall portrait. Spaun didn't hold any reason to keep a Countess Caroline Esterházy’s portrait in such a prominent place; Schwind added it to the scene because he knew about her close relationship wih Schubert. Caroline was the youngest of the two Esterházy sisters to whom Schubert had taught since 1818. It seems that in 1824, when Caroline was seventeen, the teacher fell in love with his pupil; It also seems that she felt something about him. Of course, everybody knew that such a love story couldn’t have a future, could it have been a summer love? The thing is that they remained friends until Schubert's death.

People say that Countess Caroline once complained to Schubert because he hadn't dedicated any work to her; on the contrary Schubert claimed all his works were dedicated to her. However, his only work explicitly dedicated to Caroline is the wonderful Fantasia for piano four-hands, D. 940; Since we need a song to musically illustrate this post, we will take the general dedication literally and will listen to Das Geheimnis, with a poem by Schiller, a song that tells about a secret love story. Our performers are Peter Anders and Michael Rauchausen; as usual in old recordings, the piano sounds muffled, but Anders sings so beautifully...

Sie konnte mir kein Wörtchen sagen,

Zu viele Lauscher waren wach;

Den Blick nur durft’ ich schüchtern fragen,

Und wohl verstand ich, was er sprach.

Leis’ komm’ ich her in deine Stille,

Du schön belaubtes Buchenzelt,

Verbirg in deiner grünen Hülle

Die Liebenden dem Aug’ der Welt!

Von ferne mit verworr’nem Sausen

Arbeitet der geschäft’ge Tag,

Und durch der Stimmen hohles Brausen

Erkenn’ ich schwerer Hämmer Schlag.

So sauer ringt die kargen Lose

Der Mensch dem harten Himmel ab:

Doch leicht erworben, aus dem Schosse

Der Götter fällt das Glück herab.

Dass ja die Menschen nie es hören,

Wie treue Lieb’ uns still beglückt!

Sie können nur die Freude stören,

Weil Freude nie sie selbst entzückt.

Die Welt wird nie das Glück erlauben,

Als Beute nur wird es gehascht,

Entwenden musst du’s oder rauben,

Eh’ dich die Missgunst überrascht.

Leis’ auf den Zehen kommt’s geschlichen,

Die Stille liebt es und die Nacht,

Mit schnellen Füssen ist’s entwichen,

Wo des Verräters Auge wacht.

O schlinge dich, du sanfte Quelle,

Ein breiter Strom um uns herum,

Und drohend mit empörter Welle

Verteidige dies Heiligtum!

Please follow this link if you need an English translation.

Next Mon...

Next Mon...

Comments powered by CComment