Johannes Brahms was passionate about folksongs and arranged many pieces, both for choir (a cappella or with piano) and for voice and piano. Today, we're listening to one of them, available in three versions: the first two, composed around 1864, are for mixed choir and female choir, in both cases a cappella (catalogued as WoO. 34/8 and WoO. 36/1 respectively); Today, we're listening to the third one, written for voice and piano about thirty years later and based on the previously existing: In stiller Nacht, WoO. 33/42 [In the quiet night]. It's one of the most celebrated Volkslieder by Brahms; If you don't know it, you'll understand why when you listen to it, it's really beautiful.

Sometimes it's said it's a lullaby, but I don't agree. In fact, the title of the version for female choir is Totenklage, and even though there are cradle songs which tend to be sinister, none of them would be named that way, Lament for the dead. To give you a rough idea, the four verses of the poem tell about someone who hears a lament so utterly touching that inot only he mourns but also the moon, the stars, the birds and all the beasts suffer from such great pain.

Every two verses of the poem, Brahms makes one musical strophe with an apparently simple tune and an etherial accompaniment; Listening carefully, we realize that, as usual, the song is not as simple as it seems. I haven’t been able to find out if Brahms harmonized an existing tune, if it is his or otherwise,and the most likely option though, if he modified a piece of music that already existed. Anyway, as I said, it's wonderful.

And now, I’d suggest we try an experiment: listen to the song and read the poem before continuing reading this post. At the end of the article, I'll ask you to listen to it again.

In stiller Nacht,

zur ersten Wacht,

ein Stimm’ begunnt zu klagen,

der nächt’ge Wind

hat süß und lind

zu mir den Klang getragen;

von herbem Leid

und Traurigkeit

ist mir das Herz zerflossen,

die Blümelein,

mit Tränen rein

hab’ ich sie all’ begossen.

Der schöne Mond

will untergon,

für Leid nicht mehr mag scheinen,

die Sternelan

ihr Glitzen stahn,

mit mir sie wollen weinen.

Kein Vogelsang

noch Freudenklang

man höret in den Lüften,

die wilden Tier’

traur’n auch mit mir

in Steinen und in Klüften.

In the quiet night,

at the first watch,

a voice began to lament;

sweetly and gently,

the night wind

carried to me its sound.

And from such bitter sorrow

and grief

my heart has melted.

The little flowers

- with my pure tears

I have watered them all.

The beautiful moon

wishes to set

out of pain, and never shine again;

the stars

will let fade their gleam

for they wish to weep with me.

Neither bird-song

nor sound of joy

can one hear in the air;

the wild animals

grieve with me as well,

upon the rocks and in the ravines.

(translation by Emily Ezust)

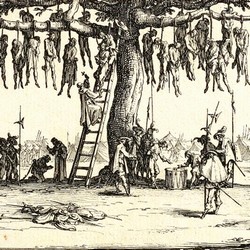

We know who wrote this poem; At least, who wrote the original poem, Friedrich Spee von Langenfeld, a Jesuit who lived between 1591 and 1635; that's to say, the end of the Counter-Reformation and the Thirty Years' War. He should have been a great preacher as he recovered many Lutheran parishes for the Catholicism Church; in fact, so many that they tried to kill him. He survived and died six years later, during one of the numerous stormings of Trier, after becoming infected with plague while he took care of the wounded soldiers.

Among the works he left, Trutznachtigall is a collection of poetry published shortly before his death, that includes a poem that originates the one musicalized by Brahms: Traurgesang von der Christi am Ölberg in Garten. Christ on the Mount of Olives. Now, we know who is suffering so much and why. Spee's poem has fifteen verses that begin with a poetic voice that hears the laments of Christ; Then, we hear Jesus' voice, who addresses God, bids farewell from Maria and shudders before the tortures that await. Finally, the last two verses tell us how nature feels sorry for him, a usual figure of Romanticism used in a mid-seventeenth-century poem. Brahms takes the first verse and the last two; The second one does not belong to Spee's poem nor do I know its origin.

Last week, I told you that I was particularly interested in Charles Cros' role as an inventor, this week there is also another poet’s side that interests me more than his poetry: his humanity, in a time of a blatant disregard for human life. One of the tasks assigned to Friedrich Spee as a Jesuit was to collect the confessions of the witches in his area before they were burned at the stake. He came out from that terrible experience with grey hair and a book published in 1631, Cantio criminalis, where he denounced the witch trials.

He demanded defence lawyers for such serious charges and held that torture was useless because it would never lead to the truth. Consequently, those delations extracted under torture weren't valid, and he warned the pious citizens who were likely to report their neighbours to the Inquisition by choicethat this could turn against them because under torture, accusations spread like wildfire. Spee condemned the cynicism of the procedure, because depending on the torture methods, confessions were considered "free" or "under torture"; he also reported that the lack of confession was tantamount to irrefutable proof of culpability. Father Spee reminded that, according to the Gospels, it was better to risk saving a guilty person than to condemn an innocent one, and concluded that those who weren't condemned by witchcraft were those that hadn't been tortured.

Needless to say, the book was published anonymously and without any authorisation; it was well received in certain circles, including the Jesuits, and eventually it had an influence on the ending of the trials. The bad news is that torture still exists in the 21st century, so the book is stillpretty much in force.

Returning to our song and the poem that inspires it, it seems to me that Friedrich Spee was pretty much aware of the meaning of the words he wrote for Christ. Now that you know the story of the poem, why don't you listen to it again?

Comments powered by CComment