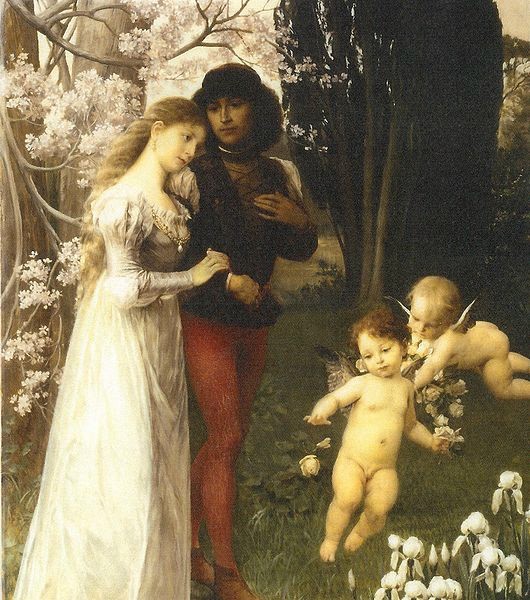

Von ewiger Liebe (Of eternal love), op. 43 No. 1 is a Lied composed in 1864 by Johannes Brahms, when he was 31 years old, in the height of literary romanticism, a movement that embodies the ideals of individualism, sentimentality, subjectivity and irrationality, with a great interest in nature and the exaltation of the figure of the hero. All these qualities are found in this poem, although in many editions it appears as the work of Josef Wenzig, it is actually August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben. In fact, Fallersleben composed this poem in 1837 from a free translation of Leopold Haupt of a Volkslieder (folk song) written in the dialect of the village of Sober, a Slavic western village recognized by Germany as a national minority.

The contemporaries of Brahms saw it as anti-Wagner and anti-Liszt, like that which against all the progressive principles of the fusion of all the arts in a total work or resolution in the music of all the arts, And against the consequences that came from these principles in the form and the musical language, he again proposed the idea of pure music in the forms consecrated by the classical tradition. For later generations, Brahms was the one who best interpreted the classicizing taste of the Gründerzeit (the era of the founders of modern Austro-German capitalism), its need for values certified by fidelity to an illustrious past. Fleeing from the self-propaganda image of Wagner and facing confrontation with Liszt refusing the conception of program music, Brahms appears as the one who picks up the classic-romantic tradition of Schumann and prints his personal label brilliantly cultivating, among the Genres that are his own, the Lied. Brahms's career reveals a solution of continuity: aware of the tradition he was designated as an heir, he could not simply welcome it, he had to critically examine it in depth and reformulate it in new terms, going back - It was throughout the history of the musical language to detect the constructive possibilities that this one offered to him. Here is the sense of Brahmanian traditionalism, much more complex and ductile than mere conservatism.

Von Ewiger Liebe, one of the prominent learner of the composer, draws musically perfectly what the text describes, being a clear example of the compositional maturity of Brahms in this genre. It begins with a distant and deepest # minor, with the melody that emerges from the bottom of the piano as if it was approached from the fog of the forest; this melody will mimic some compasses later sees everything underlined by the right hand of the piano, while the left hand maintains a figuration of corgera and setbacks that help to walk the melodic line. It is an ideal proposal to welcome the first word of the text: "Dunkel", or darkness, from which the image of a forest will emerge at dusk, without light, without sounds, not even the song of the birds. Again, a four-part proposal of the melody on the piano that will mimic the voice giving way to the characters that occupy us: a boy accompanying his loved one at home. While walking, they talk about many things, while the part of the piano continues to make the sensation of these steps among the willows.

When beginning what appears in the third sentence, again with the four bars and the melodic line on the bass, the composer offers us the first obvious change to make the boy talk. A section is started where the right hand tools, combined with the jumps and octaves of the left hand, give an image of restlessness, even urgently, drawing faithfully the anxiety felt by the boy, who She thinks the girl is ashamed of her love. This section is growing in turbulence until it ends in a songless interlude where the piano's performance is almost virtuous in the rhythmic combination and recording jumps, emphasizing the desperation of the boy.

And almost like a ray of sunshine after the storm, after a turbulent descending path of the piano, the next section emerges, which gives way to the maid. Not only does the composer give an indication of time that reduces the speed, but also changes tone, compass and pianistic texture. The words of the maid are framed in a sweet, round, flat Major flat, kind, and that calms the heart of the listener and who interprets it. At the same time, the piano's superior voice simply has a long note as if it were a pedal, or a bell, underlined by the cradle of the rest of the piano part. At the same time, the voice presents rhythmic sequences that are repeated to give unity when speaking of the maid, and little by little it is shaken slightly to emphasize the affirmation unsere Liebe ist fenster noch mehr or "our love is still it more (of firmness) ". To return to calm there is a small interlude of four bars and now, yes, we face the final line of the Lied where the maid reaffirms in the idea that iron and steel are malleable, but love Both professors are professed to be eternal and indestructible. Thus, the melody progresses sweetly led initially by pendulum movements on the part of the piano, which make small waves indecisive but that increase tension, while the melody is also rising with a spiral feeling increasingly hectic and wide , chaining one phrase after another until they explode, almost as in a climax of love, in the acute note that draws the word you say, "our", of the full statement, "our love will always last."

And after all this patient preparation of almost 8 pages of Lied and of splendidly exploding, in two systems (lines of musical text) it unloads all the tension in an almost spasmodic succession of articulated corgees of two in two in descending line as if outside the pantheon of the lovers after the love encounter until dissolving in a simple final agreement that shamelessly slows the curtain of the scene.

Not surprisingly, even Hugo Wolf, who virtually despised all the works of Brahms, had to surrender to this Lied in capital letters, marveled at his bold and bold form of emotion.

Thanks for all, Johannes.

Dunkel, wie dunkel in Wald und in Feld!

Abend schon ist es, nun schweiget die Welt.

Nirgend noch Licht und nirgend noch Rauch,

Ja, und die Lerche sie schweiget nun auch.

Kommt aus dem Dorfe der Bursche heraus,

Gibt das Geleit der Geliebten nach Haus,

Führt sie am Weidengebüsche vorbei,

Redet so viel und so mancherlei:

»Leidest du Schmach und betrübest du dich,

Leidest du Schmach von andern um mich,

Werde die Liebe getrennt so geschwind,

Schnell wie wir früher vereiniget sind.

Scheide mit Regen und scheide mit Wind,

Schnell wie wir früher vereiniget sind.«

Spricht das Mägdelein, Mägdelein spricht:

»Unsere Liebe sie trennet sich nicht!

Fest ist der Stahl und das Eisen gar sehr,

Unsere Liebe ist fester noch mehr.

Eisen und Stahl, man schmiedet sie um,

Unsere Liebe, wer wandelt sie um?

Eisen und Stahl, sie können zergehn,

Unsere Liebe muß ewig bestehn! «

Dark, how dark in wood and field!

Evening has already fallen, and now the world is silent.

Nowhere is there light and nowhere is there smoke,

Yes, and even the lark is now silent as well.

Out of the village there comes a young lad,

Taking his sweetheart home,

He leads her past the willow bushes,

Talking so much and about so many things:

"If you suffer disgrace and feel dejected,

If others shame you about me,

Then let our love be sundered as swiftly,

As quickly as we were united before.

It will go with the rain, it will go with the wind,

As quickly as we were united before."

The maiden speaks, the maiden says:

"Our love will not be sundered!

Steel is strong, and iron is very strong;

Our love is even stronger.

Iron and steel can be reforged,

But our love - who could alter it?

Iron and steel can be melted down,

But our love will exist forever!"

(translation by Emily Ezust)

Comments powered by CComment