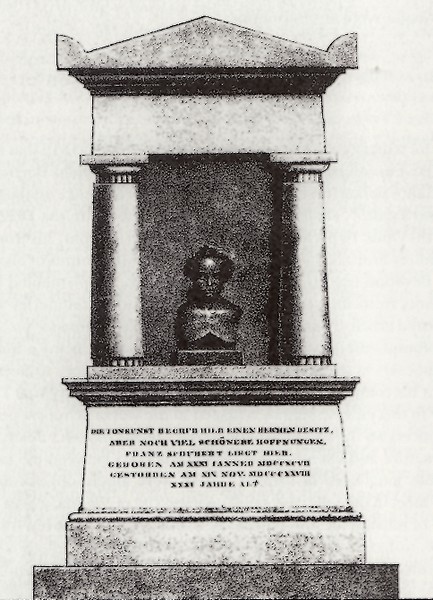

My friend also reminded me that the first person who felt sorry about those non-written works was Franz Grillparzer, who wrote Schubert's epitaph: "Here the art of music buried a rich possession, but even fairer hopes." This sentence raised to a certain controversy because some people understood that Grillparzer was underrating the works Schubert had written, although I would say he was doing just the opposite. Schumann, more realistic, didn't see the point in thinking about Schubert’s missing achievements; He had already done enough, and we should honour him for everything he had achieved. No doubt we do honour him, and the idea of writing this "post-mortem" life is certainly crazy, but... why not? At least, some notes... To start with, let's assume that Franz Schubert died on 19 November 1883 and this week we're commemorating on Liederabend the 134th anniversary of his death.

He was 86 years old, and he passed away quietly, as he had always sung in his Lieder: he took a nap after having lunch and death took him in his arms to rest after a long and worthwhile life. From that inner circle of friends, he used to gather with during his youth, only two of them were still with him: Anton Stadler, his friend since his boarding school times, who died five years later, and Eduard Bauernfeld, who died in 1890. The rest had already died; the dearest Franz Schober, just one year earlier. Grillparzer, too; someone else should write his epitaph.

I could not tell if Schubert got married and had many children, like his father, or if he lived a passionate love story, or many, or everything; I can only say that he was happy. How do I know? Because I am the one writing this story! I'm aware I'm taking a high risk here because Schubert composed mainly under pressure, but I am willing to change a frantic writing for some inner peace. So, once his youth period ended (scholars set it between 1814 and 1828), Schubert took, both his life and music, easy. Still, in more than fifty years he wrote many, many masterpieces, and he composed until his very last day. His funeral was really well-attended, thousands of Viennese filled the streets to pay their last respects to him and his many friends had no doubt that he deserved a great homage since he had been a great composer. Unfortunately, Ludwig Tietze could not sing at his funeral...

If Schubert had died in 1828, he would have appeared in History's books as the great composer fitted between the end of the Classical period and the incipient Romanticism; His long life, however, fully linked him to Romanticism, a sort of spiritual father for that generation ten years younger than him: Liszt, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Wagner. After Schubert's death, only few months after Wagner’s, the only one of this group that still lived was Liszt. They first met in Vienna in 1838, when the great pianist gave those famous concerts to raise money for the victims of Danube's flood in Hungary. Shortly before, Liszt had written the first transcripts of Schubert's lieder and had begun to play his music in Parisian salons, often with tenor Adolphe Nourrit. In that meeting in Vienna, he tried to convince him to travel with him to Paris, just for a while, to perform his music himself, but it wasn't easy to drag Schubert out of Vienna. Liszt didn’t succeed, but they kept their relationship and, of course, they met again in 1877, when a concert was organized in Vienna to homage Beethoven in the 50th anniversary of his death.

To be away was a real effort for Schubert, but many musicians used to visit Vienna, and as Schubert's fame grew, his home became a pilgrimage place. Every young composer wanted to meet him and, maybe, to get some piece of advice from the greatest composer alive! Schumann, for example, who "venerate Beethoven and Schubert most highly among all modern artists" travelled to Vienna in 1838. He visited Beethoven's grave and asked Schubert to receive him (possibly, Ferdinand, Franz's brother, who at that time was very busy classifying the scores that hadn't been yet published was in that meeting too). The premiere of Schubert's 9th symphony was arranged during that visit; since people in Vienna seemed too busy to pay attention to that masterpiece, the Great was first played in Leipzig the following year and Mendelssohn was the conductor.

And even more important: that visit and Schumann's admired praise ("whoever is not yet acquainted with this symphony, knows very little about Schubert") encouraged our composer to write the first of the seven symphonies he eventually wrote, nowadays, a must in his repertoire. By the way, many years after that encounter with Schumann, in 1865, Anselm Hüttenbrenner arrived one day at his friend's place and told him, very excited: "Look, Franz, look what I’ve just found in a drawer!" Franz couldn't believe what he had in hands, that symphony’s manuscript he gave up for lost for forty years. Hüttenbrenner explanations were quite confusing, but at the end they couldn't help but laughing before shedding tears when remembering the old days. No matter how much his friends insisted, Schubert didn't finish his work; instead, he wanted it to remain untouched, as he left it at twenty-five, his Unfinished Symphony.

We were about to run without Brahms' symphonies1 because of those seven symphonies; both Beethoven and Schubert symphonies were overwhelming, and it was too much for him, but fortunately he finally was convinced that there was room for him, too. And talking about Brahms, as he said that something could be learned from every Lied by Schubert, what would you say he did his first time in Vienna? That’s right! he called the great master. In autumn 1862, the 29-year-old man paid homage to the elder composer, who was 65; I'm sure they talked a lot about the longed Schumann. Brahms was also seen by Wagner during that first stay in Vienna, and possibly Schubert also attended that meeting, but we'll talk about their relationship next week, now we should listen to a song.

Schumann first heard Schubert's music in the summer 1827, in the salon of Karl Erdmann Carus, a friend of the Schumanns. There he met Dr Ernst Carus and his wife Agnes; Robert, seventeen years old, fell in love with Agnes, twenty-five, and in Zwickau and later in Leizpig they played together some Lieder by Schubert. Robert's diary mentions some of these lieder, among them Des Mädchens Klage. We assume that he referred to the second version of the three that Schubert wrote about Schiller's poem, published in 1826, because the other two weren't published during the composer's lifetime. We will listen to this Lied, Des Mädchens Klage, D 191, performed by Gundula Janowicz and Irwin Gage.

Der Eichwald braust, die Wolken ziehn,

Das Mägdlein sitzt an Ufers Grün,

Es bricht sich die Welle mit Macht, mit Macht,

Und sie seufzt hinaus in die finstre Nacht,

Das Auge von Weinen getrübet.

“Das Herz ist gestorben, die Welt ist leer,

Und weiter gibt sie dem Wunsche nichts mehr,

Du Heilige, rufe dein Kind zurück,

Ich habe genossen das irdische Glück,

Ich habe gelebt und geliebet!”

Es rinnet der Tränen vergeblicher Lauf,

Die Klage, sie wecket die Toten nicht auf;

Doch nenne, was tröstet und heilet die Brust

Nach der süßen Liebe verschwundener Lust,

Ich, die Himmlische, will’s nicht versagen.

“Laß rinnen der Tränen vergeblichen Lauf,

Es wecke die Klage den Toten nicht auf!

Das süßeste Glück für die traurende Brust,

Nach der schönen Liebe verschwund’ner Lust,

Sind der Liebe Schmerzen und Klagen.”

Comments powered by CComment