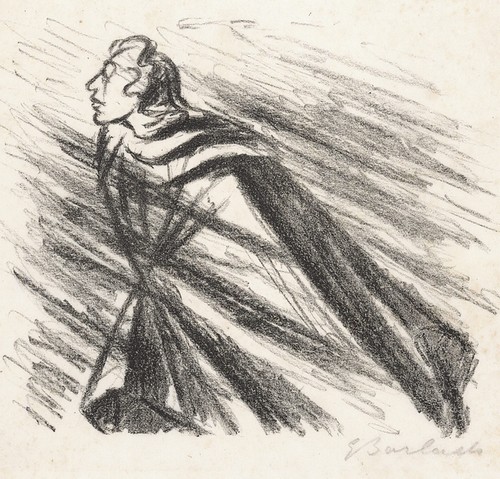

Rastlose Liebe - E. Barlach

In November 1775, J. W. von Goethe met Charlotte von Stein, a thirty-three years old lady (seven more than him) who was married with six children, and fell in love with her. She also fell for him and an intense love story began, basically, an epistolary relationship. For twelve years they wrote to each other thousands of letters, until one day Goethe went to Italy without telling her a word. She felt terribly hurt by the way he left her and urged him to return all her letters (ladies used to do that to indicate a relationship was finished and gentlemen, in turn, used to do so to prove they didn't want to endanger them); years later, they resumed their relationship, but not as eagerly as the first time. Apart from some 7000 letters written by Goethe (Charlotte destroyed hers), that love story left some reflection on his literary work, as the character of Natalie in Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship or the poem we're listening today, musicalized by Franz Schubert.

Goethe wrote it on May 6th, 1776 and I think, it's worth writing a few lines about it before we listen to the song. In the first stanza, Goethe paints a picture that Caspar David Friedrich could have signed: snow, rain, wind, fog and cliffs; all the power of nature threatening the man. Please notice that there isn't any verb in those verses; however, we sense the movement as we do in a good painting. The second stanza explains why Goethe sets this scene: to him, sufferings are easier to endure than the joys of love, and he emphasizes that by breaking the rhyme of the poem, which is always perfect except for the couple Leiden (sufferings) and Freuden (joys). In the last verse, the poet says that he accepts the misfortunes that love implies, and makes a really hyperbolic comparison: love is happiness without peace and the "crown of life". And what's that crown of life? According to the New Testament, it's one of the crowns given to believers, especially to those going through hardship because of their faith. And I say hardship but I could say martyrdom.

As I already said, Goethe's poetry deeply impressed Franz Schubert. In his memoirs, Eduard Bauernfeld says that Goethe's poems "fell as embers in the fresh, young, innocent soul of Schubert"; Bauernfeld met the composer many years after he wrote Rastlose Liebe but he's not wrong at all with this statement or when he says that "the best impression a masterpiece can make is to originate another masterpiece". Rastlose Liebe is a wonderful song, which was "a unanimous success" when Schubert performed it in an evening musical, according to what he wrote in his diary; he also wrote that “the musical genius of Goethe highly contributed to the success".

Do you remember that we’ve talked about 1815? That miraculous year when Schubert wrote one hundred and forty-five lieder. Rastlose Liebe is one of them, written on May, 19th1. That seventeen-year-old young man took the word rastlose to the letter, which can be translated as restless, and began the Lied with a frenetic six measures prelude with descending arpeggios in the right hand while the left one moves in the opposite direction; that sense of urgent and unstable movement is constant throughout the song, it only changes slightly in the second half of the second stanza. The voice also honours the expression "restless" and sings almost without pause until the third verse; there it remains silent for three measures between the third and fourth verse to prepare the end of the song.

A long end indeed, because the three final verses last twenty-seven bars, to which ten more bars are added as a postlude; all in all, more than a third of the Lied. After the last three verses, the singer repeats the last one, and then the last two, again those three together, and even three more times the last one. In all, we hear the sentence "Liebe bist du" seven times and the penultimate time, the word Liebe lasts five measures. I’m pretty sure that Schubert was trying to tell us something.

The tempo indicated in the score is "Schell, mit Leidenschaft" (fast, with passion); the manuscript doesn't specify anything else but in the first edition, published in July 1821, appears the tempo = 152. And what shall the players do with that indication? Their best, actually. Some of them respect the indications, some take it easy. My favorites are those who, as the one that we're listening today, sing a tempo but naturally, as if the passion really came from his heart. Rastlose Liebe is one of my favorites songs (I'm not at all unique, lots of people love it); I hope that if you don't know it, you fall in love with it too. Our version, that rises to the occasion, is that of Nicolai Gedda and Erik Werba, recorded live in 1961.

= 152. And what shall the players do with that indication? Their best, actually. Some of them respect the indications, some take it easy. My favorites are those who, as the one that we're listening today, sing a tempo but naturally, as if the passion really came from his heart. Rastlose Liebe is one of my favorites songs (I'm not at all unique, lots of people love it); I hope that if you don't know it, you fall in love with it too. Our version, that rises to the occasion, is that of Nicolai Gedda and Erik Werba, recorded live in 1961.

Goethe wrote it on May 6th, 1776 and I think, it's worth writing a few lines about it before we listen to the song. In the first stanza, Goethe paints a picture that Caspar David Friedrich could have signed: snow, rain, wind, fog and cliffs; all the power of nature threatening the man. Please notice that there isn't any verb in those verses; however, we sense the movement as we do in a good painting. The second stanza explains why Goethe sets this scene: to him, sufferings are easier to endure than the joys of love, and he emphasizes that by breaking the rhyme of the poem, which is always perfect except for the couple Leiden (sufferings) and Freuden (joys). In the last verse, the poet says that he accepts the misfortunes that love implies, and makes a really hyperbolic comparison: love is happiness without peace and the "crown of life". And what's that crown of life? According to the New Testament, it's one of the crowns given to believers, especially to those going through hardship because of their faith. And I say hardship but I could say martyrdom.

As I already said, Goethe's poetry deeply impressed Franz Schubert. In his memoirs, Eduard Bauernfeld says that Goethe's poems "fell as embers in the fresh, young, innocent soul of Schubert"; Bauernfeld met the composer many years after he wrote Rastlose Liebe but he's not wrong at all with this statement or when he says that "the best impression a masterpiece can make is to originate another masterpiece". Rastlose Liebe is a wonderful song, which was "a unanimous success" when Schubert performed it in an evening musical, according to what he wrote in his diary; he also wrote that “the musical genius of Goethe highly contributed to the success".

Do you remember that we’ve talked about 1815? That miraculous year when Schubert wrote one hundred and forty-five lieder. Rastlose Liebe is one of them, written on May, 19th1. That seventeen-year-old young man took the word rastlose to the letter, which can be translated as restless, and began the Lied with a frenetic six measures prelude with descending arpeggios in the right hand while the left one moves in the opposite direction; that sense of urgent and unstable movement is constant throughout the song, it only changes slightly in the second half of the second stanza. The voice also honours the expression "restless" and sings almost without pause until the third verse; there it remains silent for three measures between the third and fourth verse to prepare the end of the song.

A long end indeed, because the three final verses last twenty-seven bars, to which ten more bars are added as a postlude; all in all, more than a third of the Lied. After the last three verses, the singer repeats the last one, and then the last two, again those three together, and even three more times the last one. In all, we hear the sentence "Liebe bist du" seven times and the penultimate time, the word Liebe lasts five measures. I’m pretty sure that Schubert was trying to tell us something.

The tempo indicated in the score is "Schell, mit Leidenschaft" (fast, with passion); the manuscript doesn't specify anything else but in the first edition, published in July 1821, appears the tempo

= 152. And what shall the players do with that indication? Their best, actually. Some of them respect the indications, some take it easy. My favorites are those who, as the one that we're listening today, sing a tempo but naturally, as if the passion really came from his heart. Rastlose Liebe is one of my favorites songs (I'm not at all unique, lots of people love it); I hope that if you don't know it, you fall in love with it too. Our version, that rises to the occasion, is that of Nicolai Gedda and Erik Werba, recorded live in 1961.

= 152. And what shall the players do with that indication? Their best, actually. Some of them respect the indications, some take it easy. My favorites are those who, as the one that we're listening today, sing a tempo but naturally, as if the passion really came from his heart. Rastlose Liebe is one of my favorites songs (I'm not at all unique, lots of people love it); I hope that if you don't know it, you fall in love with it too. Our version, that rises to the occasion, is that of Nicolai Gedda and Erik Werba, recorded live in 1961.Rastlose Liebe

Dem Schnee, dem Regen,

dem Wind entgegen,

im Dampf der Klüfte,

durch Nebeldüfte,

immer zu! Immer zu!

Ohne Rast und Ruh!

Lieber durch Leiden

möcht' ich mich schlagen,

also so viel Freuden

des Lebens ertragen.

Alle das Neigen

von Herzen zu Herzen,

ach, wie so eigen

schaffet das Schmerzen!

Wie - soll ich fliehen?

Wälderwärts ziehen?

Alles vergebens!

Krone des Lebens,

Glück ohne Ruh,

Liebe, bist du!

Through rain, through snow,

Through tempest go!

'Mongst streaming caves,

O'er misty waves,

On, on! still on!

Peace, rest have flown!

Sooner through sadness

I'd wish to be slain,

Than all the gladness

Of life to sustain

All the fond yearning

That heart feels for heart,

Only seems burning

To make them both smart.

How shall I fly?

Forestwards hie?

Vain were all strife!

Bright crown of life.

Turbulent bliss, --

Love, thou art this!

Through tempest go!

'Mongst streaming caves,

O'er misty waves,

On, on! still on!

Peace, rest have flown!

Sooner through sadness

I'd wish to be slain,

Than all the gladness

Of life to sustain

All the fond yearning

That heart feels for heart,

Only seems burning

To make them both smart.

How shall I fly?

Forestwards hie?

Vain were all strife!

Bright crown of life.

Turbulent bliss, --

Love, thou art this!

(translation by Edgar Alfred Bowring)