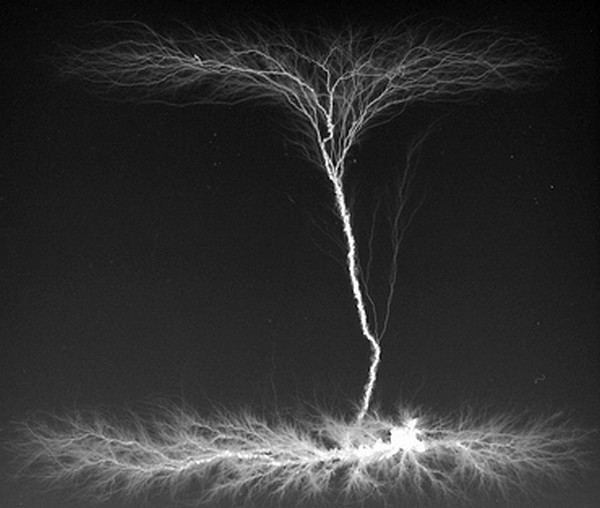

Lichtenberg figure

Some songs are love at first sight. I hear them and immediately, I have to find out what, who, when and why. Above all though, I have to listen to them over and over again. This week's song is love at first sight. Strictly speaking is love at second sight (or hearing) because while I was listening and thinking how interesting it was, it was already over (songs can be short, very short or by Ned Rorem) and I had to listen back.

O you Whom I Often and Silently Come is, in fact, a song by Ned Rorem which was written in the summer of 1957, commissioned by an amateur singer, Luke Wilder Burnap. Mr. Burnap, if I got it right he was a Broadway producer, wanted to sing the songs with his own accompaniment with the virginals, a very popular instrument at the 16th and 17th centuries but quite exotic in mid 20th century. Rorem wrote for him the Five Songs to texts of Walt Whitman, the second of which is O you Whom I Often and Silently Come. I imagine that Mr. Burnap was delighted with his songs.

Walt Whitman (1819-1892) is one of the most important US poets and he inspired over four hundred songs. Ned Rorem is one of those composers inspired by Whitman, among other reasons because "he had purveyed his most heartfelt texts." We made a first approach to this musician on this post so this time we're focusing on the poet.

O you Whom I Often and Silently Come is, in fact, a song by Ned Rorem which was written in the summer of 1957, commissioned by an amateur singer, Luke Wilder Burnap. Mr. Burnap, if I got it right he was a Broadway producer, wanted to sing the songs with his own accompaniment with the virginals, a very popular instrument at the 16th and 17th centuries but quite exotic in mid 20th century. Rorem wrote for him the Five Songs to texts of Walt Whitman, the second of which is O you Whom I Often and Silently Come. I imagine that Mr. Burnap was delighted with his songs.

Walt Whitman (1819-1892) is one of the most important US poets and he inspired over four hundred songs. Ned Rorem is one of those composers inspired by Whitman, among other reasons because "he had purveyed his most heartfelt texts." We made a first approach to this musician on this post so this time we're focusing on the poet.

The influential poetry of Whitman is collected in a single volume, Leaves of Grass, published in 1855 for the first time and edited by the author six more times. His name wasn't showed in the cover or the title page in the first edition; it only appeared in tiny type in the copyright page and, even more interestingly, as a part of the first poem. Let's the author introduce himself: "Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos, / Disorderly fleshy and sensual... eating drinking and breeding, / No sentimentalist... no stander above men and women or apart from them... no more modest than immodest."

Within Leaves of Grass, poems are grouped by sections. O you Whom I Often and Silently come belongs to Calamus; this section, first appeared in the third edition in 1860, celebrates relationships between men, what Whitman called "the manly love of comrades."Calamus is named after a mythological character, Kalamos, who is in love with another young man, Karpos. When Karpos drowns in the river, Kalamos goes so desperate that he allows himself to drown as well. His father, the god Meander, turns him into a calamus (or sweet flag), a plant that lives on the banks. So, when you hear the wind rustling through the calamus, you're actually hearing the cries of Kalamos because of Karpos's death. Perhaps because the poems were ambiguous or because the readers of that time lacked of imagination, Leaves of Grass wasn't scandalous due to Calamus but to another section, Children of Adam, which tells, in a much more explicit way, love between men and women.

Nowadays, there's still some debate about Whitman's sexual orientation; nobody doubts he had relationships with women but with regard to relationships with men, it's discussed if they were physical or only platonic. In any case, there is much love in his poems, and a good example of this is Or you Whom I Often and Silently come (the 43rd poem at the first version of Calamus and the 38th in the last, final edition). The poet describes in three verses the need of being near the wanted man and the physical reaction, that "subtle electric fire", when seeing him, let alone when rubbing him. Is it possible more accuracy with fewer words? No wonder that this beautiful poem is among the most famous of Leaves of Grass and no wonder either that Rorem's song is also among his most well-known. We're listening the elegant, passionate version of the American baritone Donald Cramm accompanied by Eugene Istomin.

O you whom I often and silently come

O you whom I often and silently come where you are, that I may be with you,

As I walk by your side, or sit near, or remain in the same room with you,

Little you know the subtle electric fire that for your sake is playing within me.

As I walk by your side, or sit near, or remain in the same room with you,

Little you know the subtle electric fire that for your sake is playing within me.

Comments powered by CComment