There are many factors that determine what music we like. Among them, anticipation: it is more possible that we will like music that we listen to for the first time if we can anticipate what will happen, either because it has points of connection with other known works (of the composer himself or of the same period, for example), or because we identify patterns.

For centuries, musical appreciations of Europeans have been linked to a musical system: tonality. Whether or not a listener understood exactly what this meant, or if he didn't appreciate the significance of certain scale degrees, intervals, or chords, his brain had began from birth to learn patterns that would allow him to face new music. Once the work began, the listener was able to intuitively know where the music would go in the long term, that there would be changes in tonality in the medium term, and that, sometimes, composers would momentarily move away from the stability tonality suggests to create a mysterious or uncertain atmosphere. It’s not that music was always the same, we know how much styles have changed over time, but as surprising, unexpected or extravagant as it was a new work, the listener could always anticipate things.

However, what would happen if the composer were to shift away from the tonality at a certain moment, and go on going further and further, and wouldn't come back? The listeners would lose their feet because they would have no anchoring point. Without the possibility of anticipating, it would be more challenging for them to enjoy the work. And this was what happened to the people who attended the premiere of Arnold Schönberg's second string quartet and lived the birth of atonality.

There was a commotion. Schönberg said years later that the audience's reaction had been understandable. He expected that some people who disliked him would protest, but there were people who went on good faith to the concert, knowing his music, and did not expect the break that they experienced. The first movement seemed to be going well, but the second one began and the laughter and scribes started, which continued throughout the third and fourth movements, as the Rosé Quartett and the soprano Marie Gutheil-Schoder professionally handled the very uncomfortable situation.

There was a soprano, yes. As Gustav Mahler had introduced movements sung by a soloist in some of his symphonies, Schönberg included two in this quartet: the third, Litanei, and the fourth and last, Entrückung. The poems were by Stefan George, a poet influenced by classical Greek forms, akin to French symbolism and English Pre-Raphaelites. He was an advocate of art for art and believed in the transformative force of beauty, and promoted a circle of artists that gathered around a magazine, Blätter für die Kunst. George was admired by Celan, Rilke, Benjamin, Adorno… and by the Nazis: he had the bad luck that his conception of art was seen with good eyes by that growing movement. George was unhappy with this appropriation, and he went into exile in Switzerland, where he died months after the Nazis came to power. Schönberg also had to go into exile at the same time, he was a Jewish composer of degenerate music, but this occurred several years after the premiere of Quartet No. 2.

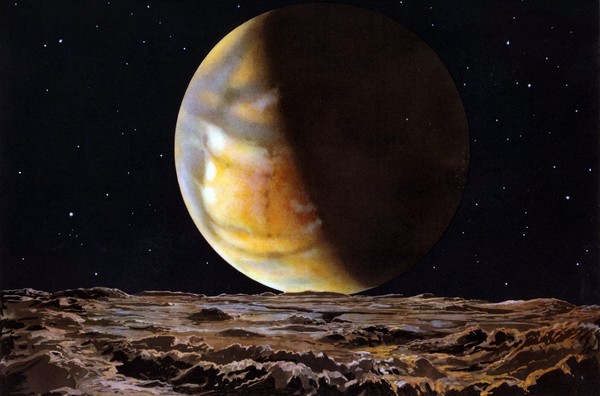

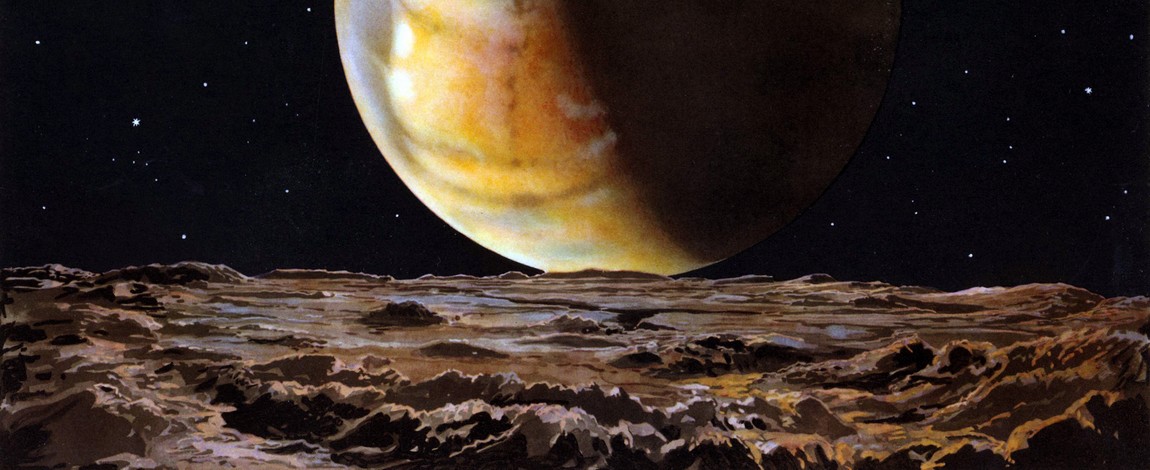

The composer wrote the first movement in March 1907, and the other three in the summer of 1908; the premiere of the work would be in December of that year. In 1907, George also published Der siebente Ring, in which Schönberg would find the texts for the two sung movements. This week we will listen to the last, Entrückung [Transcendence], which tells us about someone who leaves the Earth and moves to other planets; after an instrumental introduction that describes the departure of the Earth, the voice conveys the experience of the poetic voice.

The listeners of the 21st century are not smarter than those of the early 20th century, but we come from a different musical and cultural background. Among other things, we have been a lot to the cinema, and we have seen many science fiction films and many spaceships travelling unexplored spaces. When considering the soundtracks of this genre, it is evident that composers frequently employ atonal music; given the absence of gravity to maintain stability, it is logical that music lacks the stability of tonality. Then, when we listen to Schönberg’s quartet from our own perspective, it is consistent that when the poetic voice leaves the Earth, the music becomes atonal. In fact, the poem itself gives us a clue: Ich löse mich in tönen, kreisend, webend [I dissolve into tones, circling, weaving], and these tones can refer to both colour and sound.

Le'ts take advantage of our previous experience to enjoy Entrückung, which we will listen to performed by the Emerson String Quartet and Barbara Hannigan. Arnold Schönberg explained that at the premier, the public continued with their noisy protest for almost the entire last movement, but when the verses had finished, at the coda, the silence was made. I like to think that the complex and innovative work finally managed, in some way, to earn the respect of the audience.

Ich fühle luft von anderem planeten.

Mir blassen durch das dunkel die gesichter

Die freundlich eben noch sich zu mir drehten.

Und bäum und wege die ich liebte fahlen

Dass ich sie kaum mehr kenne und du lichter

Geliebter schatten - rufer meiner qualen -

Bist nun erloschen ganz in tiefern gluten

Um nach dem taumel streitenden getobes

Mit einem frommen schauer anzumuten.

Ich löse mich in tönen, kreisend, webend,

Ungründigen danks und unbenamten lobes

Dem grossen atem wunschlos mich ergebend.

Mich überfährt ein ungestümes wehen

Im rausch der weihe wo inbrünstige schreie

In staub geworfner beterinnen flehen:

Dann seh ich wie sich duftige nebel lüpfen

In einer sonnerfüllten klaren freie

Die nur umfängt auf fernsten bergesschlüpfen.

Der boden schüttert weiss und weich wie molke.

Ich steige über schluchten ungeheuer,

Ich fühle wie ich über letzter wolke

In einem meer kristallnen glanzes schwimme --

Ich bin ein funke nur vom heiligen feuer

Ich bin ein dröhnen nur der heiligen stimme.

Please follow this link if you need an English translation

Comments powered by CComment