Last week I told you about Hans Zincken, known as Sommer. Mathematician, physicist, director of the Technical University of Braunschweig; key piece in the family business, Voigtländer, that manufactured cameras and photographic lenses; musical promoter in his city, nascent musicologist and occasional composer.

As I was telling you back then, this changed in 1881, when Sommer left his position as director of the university (it appears that he still taught there until 1884, when he finally resigned). I would say he has left Voigtländer some years early; the relationship with his stepfather and his brother were never good, the father had died in 1878, and it's probably that he would have disinherited his stepson. Although he had his own incomes, it must not have been a pleasant situation (even less for his mother, who is never mentioned). The point is that at his forty-four he left behind his responsibilities to devote himself only to music, an unusual decision.

Hans Sommer left Braunschweig, continued his irregular musical training and learned with Liszt for a while; traveled extensively in Italy; published six more collections of lieder; got married; settled in Berlin, and since there things didn't go as he expected, he settled in Weimar in 1888. Just when the orchestra of the city welcomed a new conductor; a brilliant twenty-five-year-old Richard Strauss immediately realized Sommer's talent, and premiered his opera Lorelei, which described his father as one of the finest and most interesting things written in Germany at the moment. Sommer's successful career and his friendship with Strauss officially began at this time.

Knowing, even if roughly, how many things Sommer had done while living in Braunschweig, you would imagine that in this second period he didn't devote himself "merely" to composing. He also devoted to musicological research, continued to enrich his library and published many articles, and fought to correct the unfair and outdated system governing contracts between publishers and composers, which basically went like this: the composer sold the work and all rights by a certain amount. If sales were bad, the publisher had covered the expense; if they were good, all the benefits were for him. A few years ago we discussed this issue because one of the drivers of the new measures was Richard Strauss, but Sommer invested a great deal of time and energy to get a fairer deal for composers. He did so in his own way, reading and studying until becoming an authority in legal aspects of music life. He promoted the foundation in 1898 of the first composers' association, the Genossenschaft deutscher Komponisten, and was also its president. A few years later, in 1903, and once composers and publishers had reached an agreement, the association became the Genossenschaft deutscher Tonsetzer (the precursor of the present GEMA), whose president was Richard Strauss.

But let's return to composer Hans Sommer, who always signed his musical works with that name, leaving aside his original surname. Despite the recognition that some of his operas had, he achieved the greatest successes with his songs, which constituted much of his work; Wagnerian singers such as Eugen Gura and Karl Hill (his father-in-law) enthusiastically defended them in public recitals, at that time already quite common.

Sommer was born in 1837, that is, he was the same generation as Brahms, who was four years older. Besides, as we saw, he had been involved with him and his circle during the years of university. Later, however, he felt more affinity for what was then called the "new German school", headed by Wagner, with whom he had a good friendship, and his teacher Liszt. So, his Lieder, which he began writing a few years before Wolf, Strauss and Mahler did so, were in this direction. Our man also advanced to his most distinguished colleagues in the orchestral accompaniment; he is probably the first composer to orchestrate a complete cycle, his Op. 6, Sapphos Gesänge, which he had published in 1884 and orchestrated that same year. Sommer would admit that he would have liked his music to be more daring (he was a keen supporter of Salome after his scandalous premiere), but he eventually realized that it wasn't right for him; his Lieder remained in the late romanticism as, in fact, most of the Lieder by Strauss (who died more than twenty years later).

As so often happens, the musical world forgot Hans Sommer as the world changed. In 1922, a few weeks before his death, his last cycle was made public, twenty orchestral lieder with Goethe's poems, and someone regretted in a newspaper the oblivion that the composer suffered: "It's tragic, when a good composer is silenced while still alive."

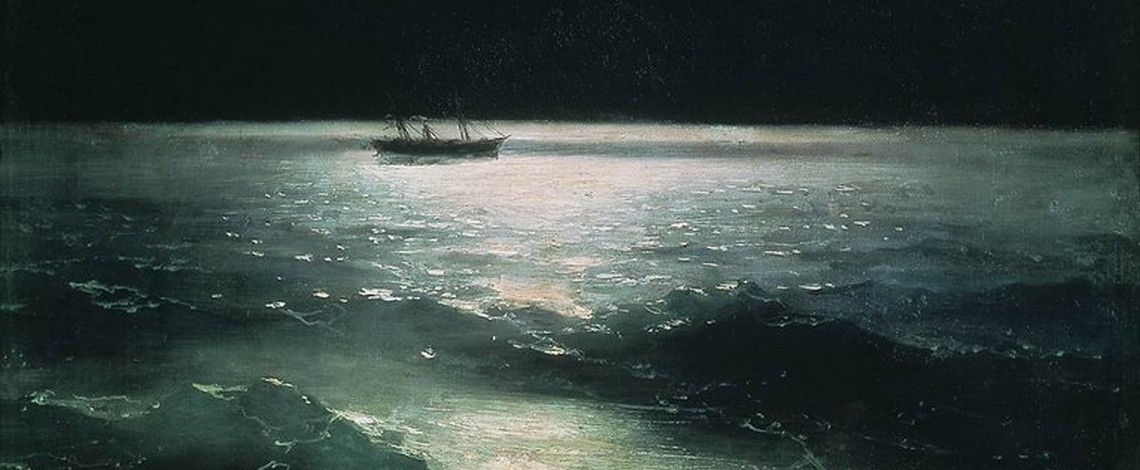

The silence has been very long; the first recordings of his work, apart from a single song recorded by Leo Slezak in the early 20th century, are of the 21st century. But now we are on the right track, so let us celebrate! Let us do so, for example, with Sommernacht, with a poem by Joseph Viktor von Scheffel, the no. 2 of the Werners Lieder aus Welschland, Op. 12, published in 1889. The performers are the same as last week, Jochen Kupfer and Marcelo Amaral. I hope you like it.

Die Sommernacht hat mir's angetan,

Das ist ein schweigsames Reiten,

Leuchtkäfer durchschwirren den dunkeln Grund

Wie Träume, die einst zu guter Stund'

Das sehnende Herz mir erfreuten.

Die Sommernacht hat mir's angetan,

Das ist ein schweigsames Reiten,

Die Sterne funkeln so fern und groß,

Sie spiegeln so hell sich im Meeresschoß,

Wie die Lieb' in der Tiefe der Zeiten.

Die Sommernacht hat mir's angetan,

Das ist ein schweigsames Reiten,

Die Nachtigall schlägt aus dem Myrtengesträuch,

Sie schlägt so schmelzend, sie schlägt so weich,

Als säng' sie verklungene Leiden.

Die Sommernacht hat mir's angetan,

Das ist ein schweigsames Reiten,

Das Meer geht wild, das Meer geht hoch;

Was braucht's der verlorenen Tränen noch,

Die dem stillen Reiter entgleiten?

The summer night has gotten to me,

I ride in silence,

Fireflies whirr through the dark surroundings

Like dreams, that once in a former good time

Made joyous my longing heart.

The summer night has gotten to me,

I ride in silence,

The stars sparkle so distantly and hugely,

They are reflected so brightly in the bosom of sea,

Like love in the depths of time.

The summer night has gotten to me,

I ride in silence,

The nightingale sings from the myrtle bush,

It sings so meltingly, it sings so tenderly,

As if it were singing of sufferings that have faded.

The summer night has gotten to me,

I ride in silence,

The sea surges wildly, the sea surges high;

Of what use are the lost tears

That slip from the quiet rider?

(translation by Sharon Krebs)

Comments powered by CComment