The wunderschöne Monat Mai passed, and we are still locked down, except for a short daily walk in time and distance (not more than one hour, not farther than 1 km), so awkward and strange it is that I wouldn't call it a walk. If you live in a crowded place like Barcelona, you’ll understand what I’m saying; if you live in a place with less demographic pressure, I hope your daily walk is more enjoyable than ours.

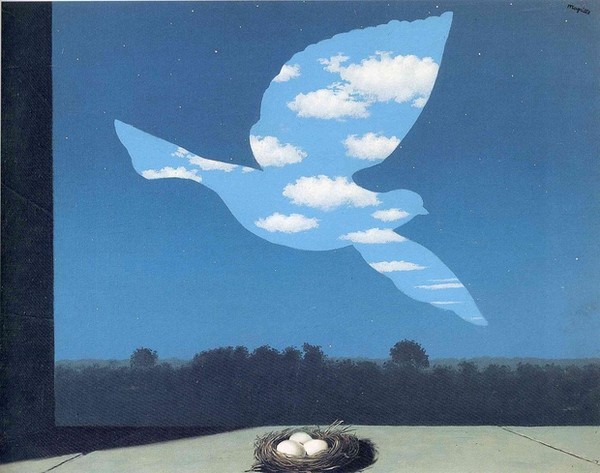

Before the month is over, I'm suggesting a third musical reading of a poem written by Ludwig Hölty in 1774, Die Mainacht [Night of May]. It's part of Sentimentalism (Empfindsamkeit) a literary movement which coexisted during the Enlightenment with the Sturm und Drang. With an elegiac tone, it features scenes of loneliness and longing, and both feelings are presented through nature: we're in a grove lit by the moonlight, and we hear the nightingales singing and the pigeons chirping. We’ve listened to Schubert's version from 1815, Die Mainacht, D. 196; later, we did it with that of Brahms, his op. 43/2, from 1866, and this week we're listening to Fanny Mendelssohn’s, her op. 9/6, composed in 1838.

We know this composer better by her maiden name than by her married name, Fanny Hensel, while we know Clara Schumann less by her maiden name, Clara Wieck. I imagine that's because they've long been known, respectively, as "sister of" and "wife of," and I truly don’t know if one way to call them is more correct than the other; it always sounded weird to me that anybody’s name would vanish after marriage. The thing is that Fanny was, as we all know, Felix Mendelssohn's sister, four years older than him. They both got the same excellent education, probably the best anybody could get in Berlin then, and lived in the same cultured and wealthy environment (their father, Abraham, was a banker). The difference between the two is that Felix could devote himself to music professionally, if he so wished, and Fanny couldn't.

A young lady of her social class could not devote herself to music professionally or to anything for the matters, but she could do it privately, at home, and that's what she did. Her parents established the Sonntagsmusiken at home in the early 1820s, musical meetings that took place at noon, on Sundays, every two weeks. There, in addition to the young talents of the family and other musicians in their circle, professional musicians used to play. They were hired in order to have a small orchestra, and the most varied repertoire was performed, including works by the house children. In 1829, Felix went to UK and Fanny got married, and the musical encounters on Sundays ended. But they returned two years later, this time organized by Fanny. She chose the repertoire, played the piano and if needed, conducted both the orchestra and the choir she had founded; a way to put her music into live, surrounded by the music of Bach or Beethoven. These meetings were often attended by soloists such as Joseph Joachim, Clara Schumann, Franz Liszt or Nicolò Paganini, a season of hers should have made more than one official programmer very jealous!

Fanny's music, however, wasn't published. Publishing was part of the professional matters that her father and brother vetoed; her mother, who like her grandmother was a great piano player, supported her, but her opinion did not count. From time to time, however, Felix gave his sister the pleasure of seeing her works published, disguised among his own; thus, in his opus 8 (from 1828) there were three lieder by Fanny and in his opus 9 (from 1830), three more.

Once married to Wilhelm Hensel, Fanny could have published her works with her husband’s permission, who didn’t object, but she did not do so because Felix and her father still opposed. Who knows how disputes in their family meetings should have been! Until 1846, nine years after her father's death, Fanny finally published. I don't know if Felix finally agreed, or if she said to him in flowery German: "My dear little brother, I love you and I respect you very much, but enough is enough!" Unfortunately, the composer died the next year. Her husband still published a few more works, but most of her work remained unpublished.

Among these posthumous works is Die Mainacht, op. 9/6, the last of the thirteen lieder with a poem by Ludwig Hölty, composed in 1838. Under the influence of her teacher, Carl Zelter, Fanny Mendelssohn composed her lieder (as Felix) following the postulates of the Second Berlin School, in strophic form and with contained spirit, and Die Mainacht is a beautiful example of this style; we won't hear any trace of the despair we perceive in Brahms's lied. As usual with pure strophic songs, the artists choose the stanzas they perform, and Soraya Mafi and Malcolm Martineau, our performers this time, chose the first three. So, we're listening to the second one, that wasn't set into music by Schubert and Brahms.

I would say that listening to different musical versions of the same poem is something we should do more often (mental note).

Wann der silberne Mond durch die Gesträuche blinkt,

Und sein schlummerndes Licht über den Rasen streut,

Und die Nachtigall flötet,

Wandl' ich traurig von Busch zu Busch.

Selig preis' ich dich dann, flötende Nachtigall,

Weil dein Weibchen mit dir wohnet in Einem Nest,

Ihrem singenden Gatten

Tausend trauliche Küsse giebt.

Überhüllet von Laub girret ein Taubenpaar

Sein Entzücken mir vor; aber ich wende mich,

Suche dunklere Schatten,

Und die einsame Thräne rinnt.

When the silver moon twinkles through the bushes,

And dusts the grass with its sleepy light,

And the nightingale pipes like a flute,

I wander mournfully from bush to bush.

I call you blessed then, fluting nightingale,

For your beloved lives with you in one nest,

And gives her singing spouse

A thousand loving kisses.

Surrounded with leaves, a pair of doves coos

Their delight to me, but I turn away,

Seeking darker shadows,

And a solitary tear flows.

(translation by Emily Ezust)

There ar...

There ar... My frien...

My frien... We are c...

We are c...

Comments powered by CComment