At the end of the 19th century, the relationship between composers and publishers was as the previous century: the composer used to sell his work for an agreed amount and he lost virtually all his rights on that work. Nowadays, the usual set-up, where the composer has more control over his work and shares the gains with the publisher, was driven by Richard Strauss, who in 1898 wrote to one hundred and sixty composers posing the need to improve their situation. His proposal was so successful that, shortly after, the German parliament approved a new law to rule the rights of composers in a similar way as the rights of writers, both in economic and intellectual conditions terms. In 1903, the first composers' rights society was established, the Genossenschaft deutscher Tonsetzer. The editors didn't like those changes at all (so we could assume that, as composers claimed, the common deal wasn't fair at all) and therefore, they got themselves organized too.

In 1906, in the middle of disputes and changes, Strauss signed a contract that included the clause which finally took him to Court: the publication of his op. 56, a Lieder collection. He was committed to grant all rights of his next collection to the same editorial, Bote & Bock. The publishers should feel very happy because although Strauss' fees were high, the profits greatly offset the investment. But Strauss didn't compose more lieder, just operas: Salome, Elektra, Der Rosenkavalier. Years passed by without any song. The publishers kept waiting until 1918; then, they threatened the composer with a demand.

At that time, Strauss had already finished the Brentano Lieder and ready to be published, but the relationship with Bote & Bock wasn't fluent; among other reasons, because they led the movement against the new copyright legislation; He knew that those Lieder would be very successful, and he didn't want the publishers to keep all the benefits. So, I can imagine him thinking: "Well, you need some songs... so be it". He commissioned Alfred Kerr, the literary critic of the Berliner Tageblatt, a few poems about the dealings between composers and publishers to musicalize them. The result was Krämerspiegel (Mirror of the shopkeeper), twelve songs which spare nobody; they portray the publisher community in a caustic way with (at that time) easily identifiable references.

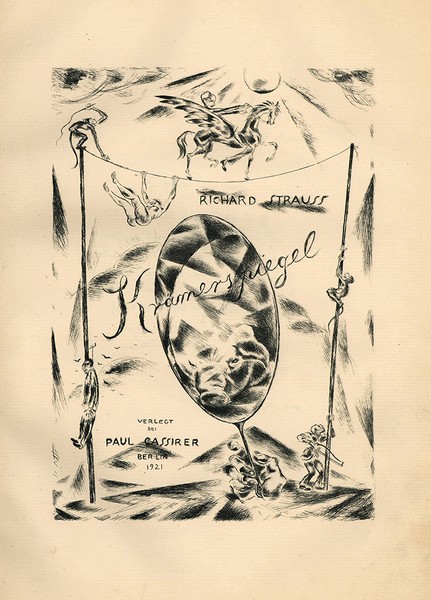

Boot & Bock sued Strauss for breaking their contract (that could not be published!) and the judge forced him to deliver to his publishers the six Lieder they demanded. He reluctantly gave them what became the opus 67, which included the three Ophelia's Lieder, and he immediately brought out the Brentano Lieder, opus 68, with another of his publishers, Adolph Fürstner. And what happened with the Krämerspiegel (which, by the way, didn't allude Fürstner)? Happily enough, it was finally published in 1921 as opus 66. The publisher was the art dealer Paul Cassirer, who made a bibliophile edition of just one hundred and twenty copies numbered and signed by the composer and the illustrator, Michel Fingesten.

The only cycle by Richard Strauss is an atypical work, and not just because the texts are commissioned or their contents; its music has nothing to do with those other two contemporary collections or with any other Lied. It's not an easy work for performers; The voice has extreme notes, wide intervals and often a deliberately ugly music; The piano part constantly changes in character and there are very long preludes, interludes and postludes that are both gorgeous, lyric music and music take the listener to a cabaret. Krämerspiegel is varied and fun and the connoisseurs of Strauss's work can easily identify auto-quotations; We even hear the fate motif of Beethoven's fifth symphony. Since it's not a very programmed cycle, don't miss it if you have the opportunity. I still remember the sensational version made by Ian Bostridge and Julius Drake a few years ago at the Teatro de la Zarzuela, It was one of those occasions that although the singer is really good, you're thrilled by the pianist. No doubt Krämerspiegel is a challenge for them!

To begin with, I'd suggest listening to the second song, Eins kam der Bock als Bote, performed by Julius Patzak and Walter Klien. It's one of the relatively easy songs to decipher. The name of the two publishers involved in Strauss's dispute appear in the title: a Bock is a goat, and Bote means "messenger". The messenger goes to the Rosenkavalier's home, where the door is blocked by a bouquet (Strauss) of roses; the English translation I'm sharing also uses the other Strauss meaning, "ostrich".

I already mentioned the story of this cycle some time ago, when I talked about Strauss' Ophelia's Lieder; it’s taken me a long time to get back to it and explain, I'm sorry! And, to finish, let me greet music publishers specially; nowadays, we know that things aren't easy for them either.

Einst kam der Bock als Bote

Zum Rosenkavalier an's Haus,

Er klopft mit seiner Pfote,

Den Eingang wehrt ein Rosenstrauss.

Der Strauss sticht seine Dornen schnell

Dem Botenbock durch's dicke Fell.

O Bock, zieh mit gesenktem Sterz

Hinterwärts, hinterwärts!

Once the goat came as a messenger

To the house of the Rosenkavalier,

He knocked with his paw,

His entry was blocked by a bouquet of roses.

With the bouquet’s thorns the ostrich quickly stabs

The messenger-goat through his thick pelt.

Oh goat, be off with your tail between your legs

Back where you came from, back where you came from!

(translation by Sharon Krebs)

Comments powered by CComment