While Mahler was composing his fifth symphony, between 1901 and 1902, his Wunderhorn time was ending. In August 1901 he finished Der Tamboursg'sell,the last Lied composed with poems from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, and that summer he musicalized some poems by Friedrich Rückert. As we know, there is a strong link between the first four symphonies by Mahler and his Lieder; For example, the first one and Die zwei blauen Augen, the second one and Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt or the third one and Ablösung im Sommer. But in the fifth symphony we don't find this link, we can no longer sing (privately, of course) any Lied by Mahler when we listen to it.

Can't we? Really? The fifth movement arrives, the horn sounds and then, what does the bassoon play? Exactly, the beginning of Lob des hohen Verstandes! This motif disappears for a while, and a bit later we hear shortly the unmistakable bray of the most famous ass in song recitals, which is repeated a little later. It seems that when Mahler resumes the adagietto, he has already forgotten his Wunderhorn song, but towards the end of the movement, the motif quoted at the beginning comes back again and again.

That's to say, the fifth symphony doesn't develop or integrate a whole Lied as the previous do, but it quotes some motifs from a song, enough to bring to our mind a story: The cuckoo challenges the nightingale to a singing competition. Everything is arranged, it has even chosen the judge, a donkey. Of course, with such big ears that allow him to hear all the nuances, he must have an excellent judgment! The nightingale sings and its developed song makes the ass dizzy; however, the limited song of the cuckoo makes it happy and it's declared the winner.

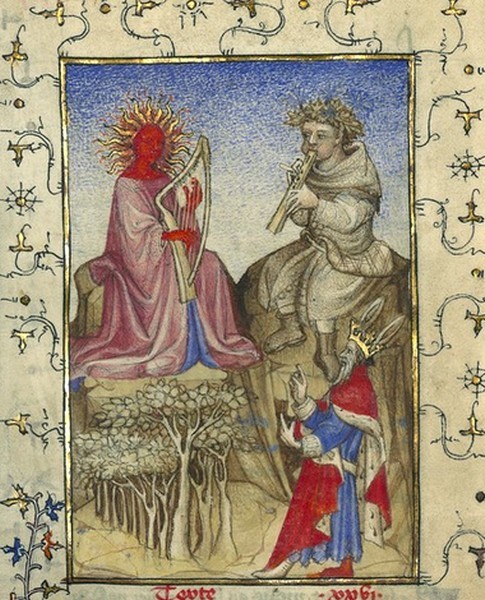

Maybe you remember a similar story but in another context: King Midas was walking in the forest when he heard an argument between two gods: Pan maintained that he played the best music with his flute, while Apolo claimed that his art with the lyre was unrivaled. Midas, unwisely, offered himself to listen to them and determine who was the better musician. Pan played his flute, and his cheerful music made the king sing and dance; Then Apollo played the lyre and Midas remained indifferent to his sophistication, so he decided that Pan was the best. Apollo, really handsome but a bad loser, punished Midas giving him the ears of an ass.

That's not the end of the story. The poor thing hid his huge brand new ears as well as he could, and he threatened with death his barber, the only person who knew his secret. The barber found the way to get rid of that burden without losing his life: he went to the bank of the river, made a hole and whispered in it "King Midas has ass's ears." He filled the hole and went home. But some reeds grow where he had buried the secret and when the wind moved them a rustling could be heard: "King Midas has ass's ears." And that way every subject knew about their king's humiliation.

It seems that this mythological story was the origin of the story of the cuckoo and the nightingale included in Des Knaben Wunderhorn that Mahler composed in the summer of 1896. He omitted the title of the poem, Wettstreit des Kukuks mit der Nachtigall ("The cuckoo and nightingale competition"), that was initially replaced by Lob der Kritik (and dedicated to Mahler's critics), but the Lied was finally called Lob des hohen Verstandes, "In praise of high intellect". Mahler used many solutions in the vocal line and the accompaniment to put us in context (the brays, the plane song of the cuckoo...) and the result is a very funny song that the performers are always willing to enjoy.

I chose to share an orchestral performance, and I'm also sharing the fifth movement of the fifth symphony, a video with the score. The conductor is the same in both cases, Leonard Bernstein, conducting the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and baritone Andreas Schmidt in the song and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in the symphony. We aware, the song is very catchy!

Einstmals in einem tiefen Tal

Kukuk und Nachtigall

Täten ein Wett anschlagen,

Zu singen um das Meisterstück:

„Gewinn es Kunst, gewinn es Glück,

Dank soll er davon tragen.“

Der Kukuk sprach: So dirs gefällt,

Hab ich den Richter wählt,

Und tät gleich den Esel ernennen,

Denn weil er hat zwei Ohren groß,

So kann er hören desto bos,

Und was recht ist, kennen.

Sie flogen vor den Richter bald,

Wie dem die Sache ward erzählt,

Schuf er, sie sollten singen.

Die Nachtigall sang lieblich aus,

Der Esel sprach, du machst mirs kraus.

Du machst mir’s kraus. Ija! Ija!

Ich kanns in Kopf nicht bringen.

Der Kukuk drauf fing an geschwind

Sein Sang durch Terz und Quart und Quint.

Dem Esel gfiels, er sprach nur: Wart,

Dein Urteil will ich sprechen.

Wohl sungen hast du Nachtigall,

Aber Kukuk singst gut Choral,

Und hältst den Takt fein innen;

Das sprech ich nach mein’ hohn Verstand,

Und kost es gleich ein ganzes Land,

So laß ichs dich gewinnen.

Kukuk, Kukuk, Ija!

Once in a deep valley,

The cuckoo and the nightingale

Had a contest:

To sing the Masterpiece.

To win by art or to win by luck,

Fame would the victor gain.

The cuckoo said: "If it pleases you,

I will nominate the judge."

And he named the donkey right away.

"Since he has two huge ears,

He can hear so much better

And will know what is correct."

They soon flew before the judge

And when the issue was explained to him,

He told them they should sing.

The nightingale sang out sweetly!

The donkey said: You make me dizzy!

You make me dizzy! Eee-yah!

I can't get it into my head!

The cuckoo then quickly started

his song through thirds and fourths and fifths;

The donkey found it pleasing, and only said

Wait! Wait! Wait! I will pronounce judgement now.

Well have you sung, Nightingale!

But, Cuckoo, you sing a good chorale!

And you keep the rhythm finely and internally!

Thus I say according to my sublime understanding,

And, although it may cost an entire land,

I will let you win!

Cuckoo, cuckoo! Eee-yah!

(translation by Emily Ezust)

Comments powered by CComment