After some weeks dedicated to the ESMUC Master's Degree in Lied, I had planned to post a new letter from our alphabet, but eventually, I chose to give priority to one more guest post. Jorge Binaghi, music critic in Mundoclαsico (among other publications), is one of those fantastic people to whom you mention in a casual way how much you’d like him to write an article and a few weeks later, you get an email explaining that as it was so hot to go to the beach, he’d stayed at home and wrote your request.

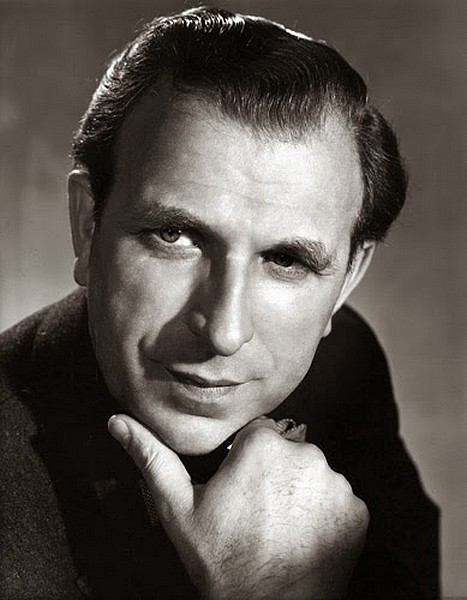

The attachment was this beautiful text that you can read following these lines; a while ago Jorge told me in the most casual way, that he had listened to Hans Hotter several times at the opera house. I was truly impressed; that's why I asked him to tell us about it. I knew his words would be moving. Here you have his impressions and his memories, musically illustrated with the last lied of Winterreise, Der Leiermann, Hotter's recording with Gerald Moore. Thank you very much, Jorge, I cannot express how thankful I am.

Hans Hotter. I listened to him live for the first time at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires in 1962. He sang the Grand Inquisitor in Verdi's Don Carlo and the three Wotan of the Wagner's Ring along with Birgit Nilsson and Grι Brouwenstijn (that was the level of the Teatro Colón back then).

At seventeen, I already knew him because of his mythical Dutchman, some arias and a little of the Wotan, from Die Walküre, that he had sung with Martha Mφdl two years earlier also in Buenos Aires.

Needless to say, Hotter was one of those singers who radiated such magnetism that neither a recording nor a video could ever equal our feeling when we left the theatre. Of course, I remember his imperial Wotan from the Rheingold (which I attended while an attempted coup to my parents' rage), but my first big impression had been earlier when the Grand Inquisitor knocked twice his cane and said 'Perchè son io qui? Che vuole il re da me?' Of course, he had a huge, gorgeous, enveloping voice, but the most significant was what he said and how he said it. And when he appeared in the second act of The Valkyrie to sing the victory song (along with Nilsson's 'Ho io to ho' which were a bugle) you were out of breath. More than out of breath you stuck to those sorrowful phrases, first in his dispute with Fricka, later with his modified orders to his daughter (the future great rebel, but with a cause). I didn't know a word of German, but I still remember his 'Das Ende ... Das Ende' in his monologue with as much nuance as desperation, or his last warning 'Sigmund fälle!'. When he reappeared at the end of the act, that disdain with which he spoke to Hunding, could have collapsed him (Arnold van Mill) as struck by lightning, and the immediate fury at the end of the second act, that foreshadowed the clouds of the third one, was frankly disturbing. Even so, I wasn't prepared (and his Wagner's duo album with Nilsson had already been released) for the third act, for the arrogance of the powerful god who knows is guilty, for the infinite love of the father when he punishes his favourite daughter. At that moment, when he said, 'freier als ich, der Gott', not knowing - surtitles didn't exist at that time, how wonderful! - his twilight was coming and that he wasn't as free as he pretended, his anguish and his sorrow could be sensed. And, still, his invocation to Loge before the curtain fell and the audience literally cheered.

His 'Wanderer' was ironic, sceptical, defeated before the final humiliation, still able to inspire dread with threats to Mime or in his last encounter with Erda.

And why am I writing this? Because Hotter went back, once again, to Buenos Aires in 1966, but that time, to offer two concerts. The first one was in a Museum, organized by a very elitist association (at that time); most people couldn't afford the sparse tickets left. Some people went shortly before the recital (a bunch of German lieder); the only one who managed to get in, came out walking on clouds (such recitals weren't broadcasted). But what eventually became his farewell from Buenos Aires fortunately took place at the Colón, on a Saturday afternoon and there, because he might have known it was his last time there, he sang THE cycle, read here Winterreise. Of course, there were and there are many recordings (or some) to that monument to human loneliness and pain by Hotter with notable accompanists (the one of Teatro Colón was right). I knew it superficially (I had come into Lied thanks to Victoria de los Αngeles' singing in 1962. She, Crespin, Gedda and Hotter were the masters responsible for my devotion to Art Song, so different among themselves, so complementary).

I cannot put into words the emotional earthquake that Hotter caused with every song. I will only say that the coughs were almost non-existent and severely repressed while that dark and enveloping voice was telling something that, happily enough, wasn't within a teenager's reach. I understood it better in the course of time, thanks to having battled hard, as that narrator who, when he arrived at Der Leiermann, created such tension and silence that it became unbearable...

Years later, a lot, I saw Hotter once again at the Liceu. His last performance there. The disgusting and ambiguous Schigolch of Berg's Lulu. I don't know why the last opportunity of him giving a recital was lost. He could have done it.

I had been a long time since I waited for singers after a performance and, foolishly, I thought there would be a crowd. We weren't such a crowd and the great Hotter was old and tired. But his eyes kept their vivacity. He was surprised that I didn't ask him for a signature -I didn't have a programme - but I told him that I wanted to thank him for everything he had done in Buenos Aires. The god reappeared. 'You couln’t have seen me on my debut'. 'No, you debuted with Flagstad, Janssen, Svanholm and Kleiber among others, in 1948; I saw you later. 'And what brought you here today? '

"Many things. Everything. Since the two knockings of the Grand Inquisitor. But, above all, the 'Leiermann' and 'Der Mai war mir gewogen'. 'Do you speak German?' 'A little. Back then I learned the sentence by heart because I didn't speak a word.' There was no sign of Schigolch anymore, hardly of Hotter's age; the majestic Wotan regained his human dimension and told me: 'That was always a special audience. I'm going to write my memoirs and I'm almost sure you'll smile when you see the title.'

He left like the Wanderer with his broken lance, but his dignity intact. As everyone knows, his autobiography was published ten years later (1996), its title was precisely that verse of Schubert's Winterreise.

Drüben hinterm Dorfe

Steht ein Leiermann

Und mit starren Fingern

Dreht er, was er kann.

Barfuß auf dem Eise

Schwankt er hin und her

Und sein kleiner Teller

Bleibt ihm immer leer.

Keiner mag ihn hören,

Keiner sieht ihn an,

Und die Hunde brummen

Um den alten Mann.

Und er läßt es gehen

Alles, wie es will,

Dreht und seine Leier

Steht ihm nimmer still.

Wunderlicher Alter,

Soll ich mit dir geh’n?

Willst zu meinen Liedern

Deine Leier dreh’n?

Comments powered by CComment