A few days ago, tenor Javier Camarena gave an all-Tosti recital at the Palau de la Música. A user from Twitter, @alegrescomares (named after The Merry Wifes of Windsor) raised some quite common doubts about song and their different types. I tried to clarify some things, with the necessarily concise format of the network; I thought later that maybe I could dedicate a post to expand my comments and review some basic concepts.

On my left shoulder, Little Devil, (didn't you miss him?), grumbled: "Really?! Liederabend is about to turn twelve, and you are explaining what Art Song is.?! Well, of course it's not a new issue. But when I read the debate on Twitter, I thought it might be interesting to focus on some points again. Little Devil kept on muttering, "You'll bore people who're already very focused." Maybe you're right. Then Little Angel on my right shoulder, who until then looked really bored, said: “What is the worst-case scenario? Perhaps some readers would prefer to skip the text and listen to the song directly?

Dear readers, I will try to respond briefly to the doubts raised by @alegrescomares and other users and will link to previous articles that can expand the different points, in case someone is interested. If you find it redundant, I understand you; please go to the end, where Tosti and Pavarotti are waiting for you. The rest, let's go!

Are all the songs, like Schubert and Tosti's, the same thing?

Not at all. The genre that was born in the German area as Kunstlied (and, to short, we call it Lied), that when it was reworked in France was called mélodie, in English is called Art Song, etc. (we could continue the journey throughout Europe), is characterized, about all, by poetry. A poem is the key to any song in this genre: a composer reads a poem that inspires him to write a song. That's it. If there is a poem, it is Art Song. If not, there is not. In case of doubt, cherchez le poème, look for the poem. There is a grey area, definitely, but if we follow this general rule, we can go safe in the musical world.

Corollary: The songs of Nena and Rammstein, even though they're both Lieder in German, aren't the same, since a song isn't just a song.

If it is not a Lied, would it be considered "second class"?

Of course, it's not, it's just a different thing. Quality does not depend on the genre.

If a song was meant to be sung at home, does that means it was poor quality?

Not necessarily. Most of the songs we hear here every week were domestic music. The performers were more or less trained and gifted, but this did not make the songs better or worse; it made the listeners more or less happy. If the composers knew who they were writing for, they made their music fit them. If not, they would go their own way, often against the opinion of the publishers, who wanted to reach a larger audience with more simple pieces.

But songs were sung at home. Where, otherwise? Perhaps some were sung, occasionally, in a chamber concert, between quartets and piano works, but Die schöne Müllerin wasn't performed complete until 1856, for example, and song recitals generalized some decades later.

Throughout the 19th century, until the outbreak of World War I, publishers were unable to meet the demand for musical scores, leading to the sale of tens of thousands of copies of the most popular scores. They published quality songs by quality composers (such as the ones we hear here), but also by willing amateurs, or by people with some musical knowledge without any artistic aspiration; these pieces vanished as soon as the copies were sold.

But the songs, were they sung only in the wealthy houses?

Not only. Franz Schubert's father, a schoolteacher, formed a string quartet with three of his sons. Sometimes they joined forces with their neighbors, creating diverse chamber ensembles. Herr Grob, a friend of the Schubert family who owned a fabric shop, had a piano at home where Schubert's early Lieder were often sung. Naturally, musical knowledge was not exclusive to Schubert's neighbourhood; just as the rate of literacy was extremely high throughout the German area, so was musical training.

And traditional songs, like El testament d'Amèlia, what are they?

There are songs of usually uncertain origin and collected with many variants, which have come to us filtered by the passage of the centuries. Many composers have arranged folksongs, sometimes with simple harmonizations, sometimes with elaborate reinterpretations. And they have done it, above all because Lied, as a genre, used the traditional song as a model; in this context, its value has always been recognized and work has been done so that it would not be lost.

All this is fine, but what about Tosti?

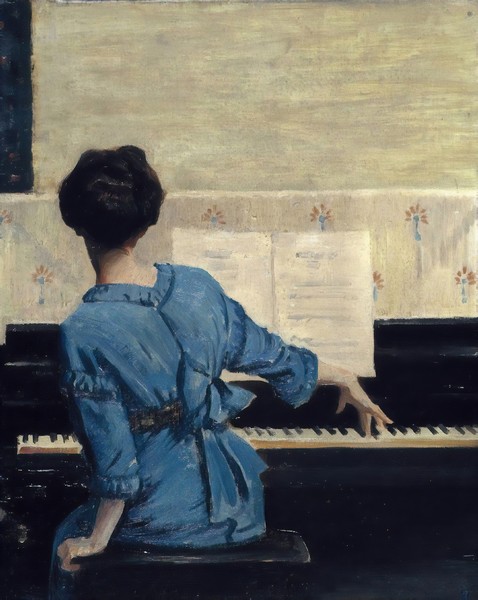

Tosti was a gentleman who deserves more than a few lines. He devoted himself mainly to the parlour songs and the romanze di salotto, that is, songs not necessarily with artistic ambition that, during the 19th century, were sung in bourgeois houses, the little nobility or the court (he lived for decades in England, closely linked to the Victorian court, and previously had been to Italian royalty), often to show the performer's skills. He also wrote songs from poems, taking care to respect his prosody and not to “deform” them and, therefore, they would fit into the lirica da camera, the Italian version of Art Song).

Tosti brought his songs to concert halls; first class singers such as Nellie Melba and Enrico Caruso sang them, and they are still sung. It is often difficult to determine which genre they belong to, except that we speak popular songs such as Neapolitans. And, to be honest, I don't worry about it. There are Tosti's songs that I love, whatever the genre.

Hello again, readers who skipped the middle of the article! Time to listen to a song. It turns out that the day after being the star at the Palau de la Música, Tosti was also present at the Liceu, at the recital of Lise Davidsen and Freddie by Tommaso, with a program of those I told you a while ago because are not my cup of tea. Given the comments I read, Tosti, between two arias of Pikovaia Dama and four great Lieder by Strauss, wasn't really appreciated. One of the songs that were heard is Ideale, with a poem by Carmelo Errico, which I love. It's our song this week, with Luciano Pavarotti and Eugene Kohn in a 1974 live performance; as you will hear, the audience was unable to refrain from applauding even before the song concluded.

Lungo le vie del cielo:

Io ti seguii come un'amica face

De la notte nel velo.

E ti sentii ne la luce, ne l'aria,

Nel profumo dei fiori;

E fu piena la stanza solitaria

Di te, dei tuoi splendori.

In te rapito, al suon de la tua voce,

Lungamente sognai;

E de la terra ogni affanno, ogni croce,

In quel sogno scordai.

Torna, caro ideal, torna un istante

A sorridermi ancora,

E a me risplenderà, nel tuo sembiante,

Una novella aurora.

Please follow this link if you need an English translation

Comments powered by CComment