Can you separate the art from the artist? A few months ago, I listened to a radio program (Musiques empoderades, Catalunya Música) where this matter was discussed. Some guests thought that the work doesn't necessarily reflect the darkest aspects of the creator's life, while others maintained that the work is part of life, and that both are inseparable. While listening to them, I doubted, because it's true that the work is part of life, and it's alto true that it does not necessarily reflect it; for example, I am not able to detect cruelty in Gesualdo's music. The same thing goes in the opposite direction: Operas such as Otello, Carmen and Wozzeck tell about sexist violence, but that doesn't mean that the authors, the performers or the audience are abusers, just as crime fiction's writers and readers don't necessarily tend to be criminals.

Back to the initial question: can you separate the art from the artist? We do it all the time: we enjoy pieces of music, paintings or novels without being influenced (for better or for worse) by personal circumstances of the creator that we don't know; it's not usual that we know the life of the artists before we know their work. If anything, we do so later; often, in this over-informed world, more than we would like. Our inner conflict begins when we discover things that we dislike, and we don't know how to react before the art. An art remains where it was always.

I think our reaction depends on the ties we have with the creator, and I will give some personal examples. I very much like the music by Richard Wagner, and I admire the creator of magnificent musical works as much as I despise and the author of the pamphlet Das Judentum in das Musik (Judaism in Music). Antisemitism was deeply rooted in the 19th century, I know, just think of Felix Mendelssohn, Heinrich Heine or Gustav Mahler, but still. However, I didn't read a doctoral thesis on Christoph Wilhelm Schütz because it was written by Joseph Goebbels; maybe some day. I also give some recent examples without mentioning the names: There are writers who tell the worst sexist or pro-Franco opinions (I put them together because there are usually together) on the social networks; I don't have any interest on reading what they write, maybe because I don't have a previous tie with them. But instead, I was saddened by a statement from one of my favorite writers, a person I really liked; what he said was disrespectful to many people and a lie, it can be easily proved. It was a matter of ignorance or bad faith, and since he is a very cultured gentleman, my admiration vanished.

And what about the #metoo movement? One of my favorite actors was accused; I didn't closely follow the case, because I didn't need to know the details. However, I saw one of his films not long ago. I don't know whether he is guilty or not guilty, but he is a great actor. And then, there's the case of a certain singer who admitted that the accusations were true (yes, that great singer), who recently got a long ovation after a concert. In recognition of his art? I could understand it (but I find it inopportune). To support it? I do not understand it at all.

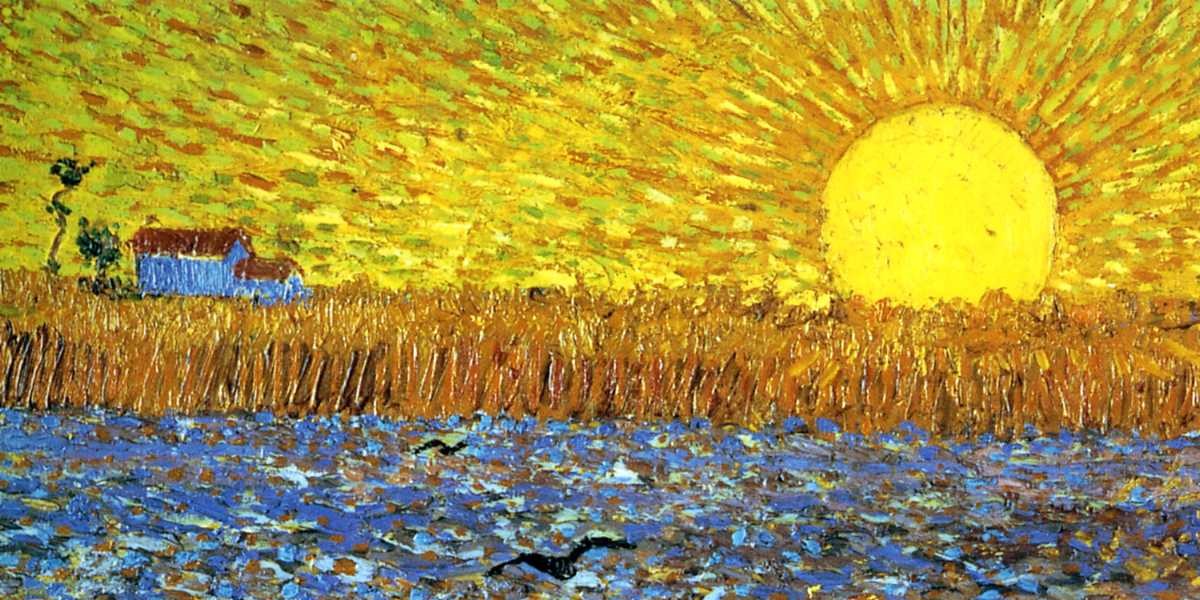

You wonder which persona non grata lies behind our song this week. Here you are: Gabriele D'Annunzio (his real name, Gaetano Rapagnetta, doesn't ring so well), considered by many to be the greatest Italian poet since Dante and also considered to be the father (inspiring, creator) of Fascism. A simple search on the Internet and you want to get out fast, but we are interested in his poetry; in particular, in the around forty poems that Tosti set into music. Last April marked 175 years since Paolo Tosti's birth, and I jotted down in my notebook one of his romanze di salotto, one of the best known, L'alba separa dalla luce l'ombra, with a poem by D'Annunzio. It's a song I link to the summer, probably because of the way the sun rises, highlighted by Tosti with the long high note on the word "eterno". I like the song very much, but I find Fascism repugnant; that's why I shared my mixed feelings about art and artists. This time, I separate the art from the artist.

L'alba separa dalla luce l'ombra is the second of the four Canzoni d'Amaranta, composed in 1907. It is a bright Italian song, with a broad vocal line, carefully written to favor the intelligibility of words, as the genre demands; it follows the usual rule "a syllable, a note", with virtually no ornamentation. It is a demanding piece, an opportunity for the singers to shine, and it was recorded by many celebrated tenors during the 20th century. But when I listen to these performances, I often feel as if Radames had arrived (for non-operatic people, he's the tenor in Aida), they sing with the same energy. And you don't need so much energy to sing at dawn, when everything is still; at the score, Tosti indicates "con anima" (with soul), and we find the first forte in the last verse. I finally chose a 21st-century performance, also by a great tenor, Juan Diego Flórez. I loved it from the first sentence, delicate and, indeed, with soul; it's a unaffected version, sung with the apparent easiness that is Flórez's trademark. Pay attention to the first sentence of the third stanza, and to how he elaborates the crescendo until he reaches the end. I would say that Flórez does a great job!

I'm not sure about the orchestral accompaniment of the Filarmonica Gioachino Rossini and conductor Carlo Tenan; I would say it isn't the usual, but I wasn't able to find more information.

I hope you enjoy L'alba separa dalla luce l'ombra and the singing of Juan Diego Flórez!

L'alba sepàra dalla luce l'ombra,

E la mia voluttà dal mio desire.

O dolce stelle, è l'ora di morire.

Un più divino amor dal ciel vi sgombra.

Pupille ardenti, O voi senza ritorno

Stelle tristi, spegnetevi incorrotte!

Morir debbo. Veder non voglio il giorno,

Per amor del mio sogno e della notte.

Chiudimi, O Notte, nel tuo sen materno,

Mentre la terra pallida s'irrora.

Ma che dal sangue mio nasca l'aurora

E dal sogno mio breve il sole eterno!

Jac...

Jac...

Comments powered by CComment