The title of this post should be familiar to the regular readers, it indicates that I'm handing over this weekly space to a student of the ESMUC Master in Lied. As I told you last week, we're collaborating for the fourth time in a row with the subject "Literature of the genre. Repertoire of the German lied", taught by pianist Viviana Salisi. Our first guest is pianist Elena Cid, who takes us back to those times when we talked about buggy songs. Thank you very much, Elena!

All Lieder talk about you. About you, About me, about us… With Lieder, it happens as with fairy tales, that if we stop to look at them carefully we find a metaphor of life itself. This is one of the things I experience more and more as a Lied student. And that is what happens with the Beethoven song that I am going to comment on.

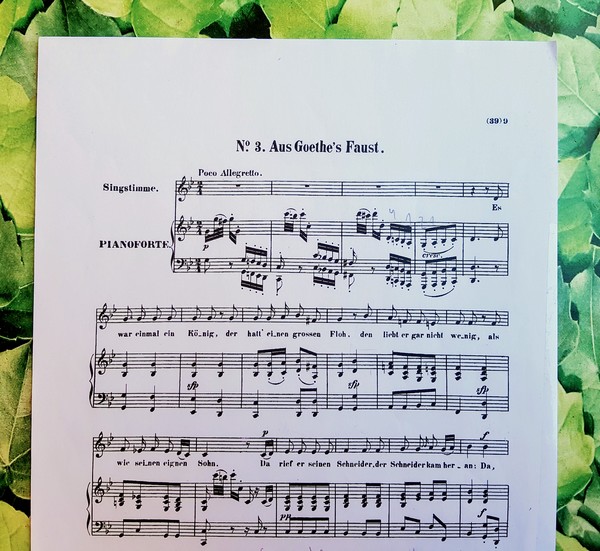

It is the Lied Aus Goethe’s Faust, (From Goethe’s Faust), better known as Floh Lied (Flea Song) or Es war einmal ein König (Once upon a time, there was a king).

In my life I have had few encounters with fleas, but enough to know how annoying they can be. One of them was a summer when we did a house exchange with a French family. They lived in a very artistic house, on a hillside overlooking a navigable canal. A beautiful site and a house on several levels, all made of wood and carpet. They had a nice white upright piano and a young Siamese kitten. After a few days of being there, black dots began to appear, jumping from one place to another. At any moment, a tiny and bouncy visitor could appear among the white sheets, on the piano bench, sliding through the staves of my scores and jumping on the keyboard.

My dear fellow master student, Juan Pablo Sandoval, was the one who discovered this work for me. He proposed that we study it together on the occasion of Beethoven's 250th anniversary. The situation we are experiencing with this pandemic has made me return to it. There is a parallelism between the two: it is an insignificant living being that takes on an excessive role in the song court; and it is a virus, a microscopic being, which has put the world's population, even the richest countries, in check with all its scientific advances.

In Goethe's Faust, Mephistopheles (the devil) sings this ballad in a tavern in Leipzig. There the locals, who drank and sang lively, ask the newcomers for a song too. Mephistopheles responds that they have just arrived from Spain (precisely!), the beautiful country of wine and its songs, and sings the song of the flea. It is the story of a king who had a flea whom he loved as his own daughter. He dresses her in tailored suits, appoints her minister, and brings her entire family to court, regardless of the ordeal it causes the queen and all members of the court.

The choice of this text and the way to put it into music take us into Beethoven's sense of humor, which is not exactly his best-known facet - he always seems to be angry in portraits. The situation narrated is ridiculous, but underneath it there is a moral satire on how an insignificant being becomes important, even untouchable, under the protection of a powerful person. This fits me more with Ludwig's frown. He probably felt identified when reading the story and called to put music on it. What insignificant being would Beethoven be thinking about when composing the song?

In 1792, when he started working on this Lied, Beethoven was 22 years old, and he was not experiencing an easy situation. His mother had died in 1787 and his father became an alcoholic and ended up in jail. He had to support his younger brothers by playing the violin in an orchestra and teaching piano for five years, while his father remained in prison and eventually died in 1792. That year he finally was able to move to Vienna and embark on his career as a successful composer. The Lied of the flea was published in 1809, within the 6 Lieder op. 75, three of them with texts by Goethe. Two years later, he would meet the writer in person through a mutual friend, who made them meet at a spa. After this meeting Goethe attested to the composer's talent ... as well as his bad mood.

But let's see how Beethoven shapes the satirical character of the story. It's amazing how he achieves it with such simple and yet so effective musical elements.

The Lied is structured in three stanzas and a coda, through which the story narrated by Mephistopheles unfolds. The musical portrait of the flea is the first humorous element that we perceive when listening to the song. It appears on the piano at the beginning and end of each stanza, with fleeting figures jumping on the keyboard. The insolent flea repeats the singer's last sentence with notes of decoration and trills added as a mockery. In the third stanza it will be the choir, real or imagined, who does this repetition overcoming the flea's little voice. Contrasting with the sound of the flea, the singer's voice sounds low and marches at a slower pace. The accordic piano accompaniment adds medieval resonances. The narration thus takes on a regal and apparently solemn tone. The singer abandons that tone at the coda to laugh openly at the absurd and repeat faster and faster: "We scratch and kill them as soon as we are stung."

The song is in minor mode, however both the singer and the flea end the last sentence of each stanza with a major chord. This brushstroke of major mode communicates to our ears that the gravity of minor mode is a comedy. The joke is confirmed in the ending, when the alternation with the major mode is accelerated until it stays in the G major chord during the last four bars. Finally, the pianist is heard chasing the flea on the keyboard until he crushes it. This was what Beethoven must have imagined when he indicated that the pairs of demisemiquaver s at the end should be both played with the thumb, giving rise to the gesture of crushing the flea on the keyboard.

On the other hand, the composer offers us a graphic joke: the notes that correspond to the flea, semiquavers and demisemiquaver, are accompanied by staccatto dots, making them look like fleas jumping through the music paper. This part of the joke is enjoyed by the performers, since the public does not usually see the score.

Regarding iperforming aspects, I would like to point out the difficulty of choosing a tempo that satisfies both the rhythm of the narration and the rhythm of the flea. In the version of Fischer Dieskau and Jörg Demus shared in another post of this blog, the tempo opts for the rapid movement of the flea and the narration is a little accelerated for my taste. At that time, the pianist demonstrates great virtuosity when jumping lightly and accurately on the keyboard at high speed. Although perhaps the biggest challenge is the one that awaits the singer in the final coda, which is a real tongue twister. It would be like repeating faster and faster “ Tres tristes tigres comían trigo en un trigal” Can you imagine a German saying this phrase extremely quickly and perfectly in Spanish and also singing? That's the difficulty of the hilarious finale, especially for the singer whose mother tongue is not German. Still, this is not the only reason why we chose a slower tempo to play it. We cannot imagine Mephistopheles in the tavern singing the story in a hurry, but taking his time to taste the tone and the words with which to captivate his listeners. The indication Poco Allegretto at the beginning of the score seems to reaffirm our idea.

I propose to listen to the version of Andreas Schiff and Peter Schreier. Not only because they coincide with my opinion in the choice of tempo. What caught my attention at first was the liveliness of the flea in Schiff's hands. It articulates the high-pitched voice of the flea with its trills and bites with great resolution and a very bright color. So much so, that I perfectly imagine the flea, proud and cheeky under the protection of the king, jumping in pirouettes and making fun of everyone. For his part, Schreier seems to me an excellent narrator, because he sings as naturally as if he were speaking. It makesthe story alive in our imaginations. He changes the color of the voice according to the moment of the narration, such as when the king speaks. I like how he emphasizes key words by highlighting some consonants and reserves the most expressive breaks in the voice for the final stanza, when he recounts the sufferings of the ladies and gentlemen of the court undergoing the flea infestation. After having listened to his version several times I have come to the conclusion that they really do make a masterful performance.

About the author

Elena Cid Iriarte is a pianist born in Malaga and is currently studying the Master in Lied at ESMUC in Barcelona.

Es war einmal ein König,

der hatt’ einen goßen Floh,

den liebt’ er gar nich wenig,

als wie seinen eignen Sohn.

Da rief er seinen Schneider,

der Schneider kam heran:

Da, miß dem Junker Kleider

und miß ihm Hosen an!

In Sammet und in Seide

war er nun angetan,

hatte Bänder auf dem Kleide,

hatt’ auch ein Kreuz daran.

Und war sogleich Minister

und hatt’ einen goßen Stern,

da wurden seine Geschwister

bei Hof auch große Herrn.

Und Herrn und Frau’n am Hofe,

die waren sehr geplagt,

die Königin und die Zofe

gestochen und genagt.

Und durften sie nicht knicken

und weg sie jucken nicht.

Wir knicken und ersticken

doch gleich, wenn einer sticht.

There once was a king

who had a large flea

whom he loved not a bit less

than his very own son.

He called his tailor

and the tailor came directly;

"Here - make clothing for this knight,

and cut him trousers too!"

In silk and satin

was the flea now made up;

he had ribbons on his clothing,

and he had also a cross there.

And had soon become a minister

and had a large star.

Then his siblings became

great lords and ladies of the court as well.

And the lords and ladies of the court

were greatly plagued;

the queen and her ladies-in-waiting

were pricked and bitten,

and they dared not flick

or scratch them away.

But we flick and crush them

as soon as one bites!

(translation by Emily Ezust)

Comments powered by CComment